Document theory and communication models

Summary: The study aims to find out whether and how important conceptual reference models of social communication: Shannon-Weaver’s model of the general communication system, Jakobson’s model of language communication, and the conceptual model of bibliographic information IFLA LRM can contribute to the formation of the document theory. Using the results of the analysis of these models, an own working model of the document is created, within which a solution to the relationship between the notion of document and the related concepts of information, information resource and medium is proposed, and the possibility of modeling the granularity and typology of documents is assessed.

Keywords: document, medium, document theory, communication models, IFLA LRM

Introduction

This study is a loose continuation of our review study presenting major document theories (Kučerová 2021). We will complement the perspective of document through the lens of scientific theories with the point of view applied in the reference conceptual models of social communication.

We will look into document in the framework of social communication. It is evident that the key role of documents is to facilitate communication in society, and in the current stage of development of information and communication technologies documents are often a precondition, without which communication would not be possible at all. Therefore, we believe it is useful to define document in the context of social communication. In our opinion, developing a model is the most promising method of the research methods profiled in social communication and it is applicable in the field of information science. It can be stated that models are among the scientific research methods that not only effectively interconnect empirical and theoretical knowledge within a given discipline, but are also a highly effective tool for interdisciplinary communication of knowledge and cooperation of scientific disciplines to address complex problems, thanks to their emphasis on a concentrated and simplified representation of a phenomenon being examined.

The aim of the study is to assess whether and how models of social communication can contribute to the formation of the document theory. Using the results of the analysis of selected models, we will try to design our own working model of document. While we applied the method of literature research in the previous article, this study is based on the method of conceptual analysis of communication models and on conceptual modelling.

The paper is divided into four parts. The first part defines the conceptual and theoretical framework of the study and characterizes the methods applied. The second part documents the course of the analysis of communication models: the requirements for the definition of the document are summarized, three selected communication models are briefly described, and the result of their conceptual analysis is presented in the form of derived concepts and their working characteristics. In the third part, we offer the definition of the term document through a model in the form of a class diagram in UML and its partial verification on real-life cases. The fourth part is devoted to discussion and consideration of possible further research directions.

1 Conceptual and Theoretical Framework of the Study

Documents pervade all spheres of practical and theoretical human activity, and therefore the scope of disciplines that can contribute to the understanding of the concept of a document is virtually unlimited. In order to achieve the set goal, however, it was necessary to adopt certain restrictions: 1) we will view the document as a part of communication in society and 2) we will narrow the conceptual and terminological basis employed down to the disciplines that form the theoretical background of the social communication models analysed.

In the first section of this chapter, we will define the concept of social communication for the purposes of our study. In the following section, we will explain why we have decided to use the term "document", or why we consider it relevant even in the current development stage of information and communication technologies. The third section is devoted to the description of the methods used, i.e., conceptual analysis and conceptual modelling.

1.1 Social Communication

In this part, we will set out the basic outline of thinking about social communication, which we will apply in our study. In Part 2, we will observe how this outline is further developed in the analysed models, which complement it with other important aspects.

Communication generally involves transmission through space (transfer) or time (preservation, transmission), allowing connection or sharing in order to access a resource. The process of communication always takes place in a certain context, it has a defined starting and ending point and an entity that is made available by transmission or sharing.

Social communication is a specific type of communication whose context is formed by society and the starting and finishing points are people. Connecting people and sharing messages is considered a condition for the existence of a company and any joint activity and cooperation. The connection can be direct (for example, a face-to-face conversation) or indirect (for example, an online conversation via Skype or a communication between the author and the reader through a book). It is clear that documents play an important role in indirect communication.

A certain terminological problem is represented by an entity made available during social communication, for which different terms are used in specific contexts and discourse communities. In the models we have selected for analysis, we will encounter the terms message, communication, and content. It can be concluded that in the same sense in which these terms are used in social communication, the term information is usually used in information science[1]. Although each of these terms has its own specifics, we will consider them synonymous for the purposes of our study. For the sake of uniform nomenclature in this study, we consider it necessary to prefer one of them and then use it consistently throughout the text.

Since definitions of a document applied in information science usually include the term information[1], this term is preferred. However, one may object to its arguing that not everything that is communicated in society is information, and not all documents serve their users as a source of information.[2] The group of "non-informative" includes a large part of artistic creations and entertaining documentaries (dance music, board games, poetry...), as well as so-called performative documentaries (for example, advertisements whose aim is not to inform about goods, but to get the customer to buy them).

After considering the applicability of each term for the purposes of this study, we decided to prefer the term content. The basic outline of thinking about social communication is therefore defined as the transfer of content between people within society.

1.2 Terminological Considerations: Why a "Document"?

The starting point of our reasoning is determining the need to find an apt designation for the term, which we have so far preliminarily characterised as a tool of indirect communication of content. This term assumes a sufficiently broad and expandable extension to cover all past, present and future types of means of communication. At the same time, it is necessary for the name to have a sufficiently specific intension that prevents including among its instances any entities that do not serve social communication. The fact that we are far from a consensus on such a term is eloquently evidenced by the note to the entry document in the ISO 690 standard (2021, 3.13): "In some professional usage, documents are referred to as 'medium', 'title' or 'item'. In library practice, the terms 'publication', 'resource' and 'information resource' are also common."

In some fields, the issue of finding an optimal term is resolved by adopting terms that originally denote narrower terms limited to a certain type of communication media. These terms are then used to convey two meanings: 1) in the original specific meaning, and 2) in an artificially expanded extension covering other types, such as images, sound recordings, performances, databases, etc. For this purpose, both "traditional", relatively semantically stable terms and "modern" terms are used, which are generally understandable thanks to the mass spread of information and communication technology. The most frequently used terms are text, which is used mainly in literary science and other humanities disciplines (Beard 2008, Lund 2010) and book, a traditional term for librarianship. Just to name a few, let us recall that the first three Ranganathan's laws of library science are worded as follows: "Books are for use; Every reader his/her book; Every book its reader" (Ranganathan 1931) apply to all types of materials in libraries. Paul Otlet also considered it useful to supplement his broadly focused Treatise on Documentation with a subtitle A Book about a Book (Otlet 1934). A similar broadening of meaning is automatically assumed for the terms bibliography, bibliographic description or bibliographic control. Other terms with such broadened extensions include publication, record, or in Patrick Wilson's words, "writing and recorded speech" (Wilson, 1968, p. 6) and data, or collections of data (database, dataset or data set).

The second method of dealing with the broad extension of an entity being defined is to use terms denoting general umbrella terms such as material, work, piece of work, creation, medium, title, item and currently probably the most widespread term source/resource, which are able to encompass all types of communication tools, but also include entities other than communication media. An example is the definition of a resource in the Internet standard RFC 3986, which defines a generic syntax for URIs, in which a resource is considered to be any concrete or abstract entity identifiable by a URI. Also, in the language of RDF (Resource Description Framework) for describing resources in a semantic web , anything that is described in this language, or that can have a property, is referred to as a resource. Robert Glushko explains that "resource has an ordinary sense of anything of value that can support goal-oriented activity" (Glushko, 2016, p. 36). In this way, the term resource is close in meaning to the concept of asset, which is "anything that has value" according to ISO 690 (2021, 3.3).

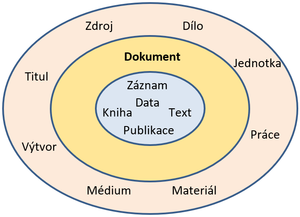

Fig. 1 Alternatives to the term "document"

In Figure 1, the three overlapping ovals schematically illustrate the semantic range of alternative concepts to the concept of document: the concepts of text, book, publication, record, and data, located in the central oval, have a narrower scope, and the concepts of work, item, piece of work, material, medium, creation, title and resource in the outer ring exceed the meaning of the term "document". In fact, the relationship among these concepts is, of course, much more complex, as their meaning often overlap, at times to the level of synonymy. Also, the understanding of their meaning often varies, depending on the specific context and discourse community using them.

We will briefly discuss the relatively frequent term information resource, which is used mainly in the discourse community of information science. The adjective "information", seemingly specifying the general term resource, brings about another issue – even if we were to disregard the fact that it is determined by the highly ambiguous and difficult-to-define concept of information and would incline towards the common understanding of information as meaningful information concerning reality, such a specification in the sense of what we have mentioned in section 1.1 is, on the contrary, too narrow and excludes numerous entities communicated in society.

Compared to the alternative concepts mentioned above, the concept of document seems more appropriate. We agree with Hana Vodičková, who expressed such opinion in 2007 when she was considering Czech equivalents for the English term manifestation from the FRBR model (Vodičková 2007). We believe that the document theories by Suzanne Briet, Paul Otlet or Michael Buckland, which we presented in the review study (Kučerová 2021), convincingly demonstrate that the concept of document has a sufficiently broad extension to cover all types of social communication tools. For these purposes, there is no need to artificially expand its extension, as is the case with the metonymic (pars pro toto) use of the concepts of text, book, publication, record, data, and information resource. At the same time, the concept of document has a sufficiently specific intension that enables exclusion of entities that cannot be considered tools for communicating content. This is its advantage over the concepts from the second, general group, which have such a wide-ranging extension that they can be used to designate practically anything. In addition, the concept of document is characterized by its semantic power to cover electronic and multimedia resources without the need for any terminological modifications as in the case of e-books, hypertext, online resources, big data, or new media. It seems that thanks to its extension and intension, the concept of document may readily include media that will be involved in the communication environment in the future.

1.3 Methodology of Conceptual Analysis and Conceptual Modeling

In the above-mentioned review study (Kučerová 2021), we divided document theories by their prevailing methods into theories using the method of categorization, the method based on specification of properties, and the method of specification of aspects. We will now add the method of modeling to the three generally used methods. We have dealt with the issue of conceptual modeling in detail in our paper (Kučerová 2018), here we will only give a brief summary.

A model is a deliberately created representation of an object or phenomenon or event (the so-called original) having correspondence to the same in essential properties. A conceptual model is a type of model with a purpose of semantic representation of the original through concepts and their relationships. A distinction is made between subjective (mental) conceptual models created during human thinking and objective conceptual models in which concepts are explicitly expressed in a formal semiotic system. Objective conceptual models are usually expressed textually (e.g. in the form of classification schemas, thesauri, metadata schemas, ontologies) or graphically (e.g. using semantic networks, entity and relationship diagrams, or class diagrams), or a combination of textual and graphical notation. A conceptual reference model is a conceptual model at the highest level of abstraction, which expresses a consensus on the meaning of basic concepts in a domain, thus enabling communication within that subject area. It provides a general framework and conceptual basis for the creation of specific (e.g., domain, implementation, technology or data) models, standards, or application profiles.

Conceptual analysis is such an analysis of a phenomenon under examination resulting in a representation of the reality analysed by means of concepts. Anything can become the subject of analysis, including concepts. Models that are an outcome and a tool of knowledge of a phenomenon can also become an independent source of knowledge and can therefore be subjected to conceptual analysis. This is also the case of our study, in which the concepts included in social communication models are analysed and interpreted. From the wide range of possibilities of using models in research (knowledge of the original, design or creation of the original, influencing the original, experiments, hypothesis testing, etc.), we will choose a conceptual analysis of selected models, which will be directed to the selection of concepts applicable in the creation of a document model. This corresponds to the choice of the models analysed: all three models can be categorized as reference models, whose function is, among other things, to serve as a source for the creation of specific domain models. We will divide the procedure into three steps: 1) we will determine the criteria of the analysis using a systematic approach, 2) we will search for terms corresponding to the set criteria in the models of social communication, and 3) we will design our own conceptual document model using the concepts obtained by the analysis of social communication models.

To design the conceptual model, we will use the form of a class diagram in the unified modeling language (UML). In this diagram, concepts are represented through classes, in which elements having the same properties are grouped. Classes are connected by three types of semantic relationships: the relationship of association represents a semantic connection, a relationship of partitive hierarchy connects the whole and its parts, and a relationship of generic hierarchy connects a class-type with its subtypes. This type of relationship is based on common characteristics – the "child" class at the lower level shares characteristics with the "parent" class at the higher level, and usually differs from the latter by its specific characteristics. The generic relationship hierarchy allows transitivity or transfer of properties, which means that a property once defined at a parent level becomes a property of all entities at child levels. In the opposite direction, it is an abstraction – towards the superordinate level, the individual characteristics of the subordinate entities are omitted, leaving only those that are common to the whole group. This achieves an effective capture of the modeled phenomena without duplication and redundancy, thereby a significant simplification of the model.

2 Analysing Models of Communication

The first part of this chapter defines some criteria of the analysis, the second part describes the selected models, and the third part presents the result of their conceptual analysis.

2.1 Criteria for Analysis: A Systematic Approach to Document Definition

In this part, we will set out the criteria for conceptual analysis of the selected social models of communication. We will not be interested in how successfully a model represents social communication in the analysis, but in what parts of the model can be used for theoretical reasoning about document. Therefore, we will focus on the criteria applicable to defining a document.

Given the different ways of defining a document, it will first be necessary to decide what type of document definition we aim for. In addition to the classical Aristotelian definition through the determination of the nearest genus and specific differences, alternative types of definitions can also be commonly encountered in the professional environment. Enumerative definitions, or definitions by listing elements represented by a concept, occur in practice in the form of numerous lists of document types. Descriptive definitions in the form of a list of properties of defined entities are well known in the library environment; bibliographic description rules explicitly specify which properties of a document are to be described, i.e., populated with values during the cataloguing process. Metaphors and metonymy are another popular tool for defining a document, detailing a defined object in the form of analogy (a document as... sign, function, medium, thing, etc.). In all these cases, however, the integration of the entity defined into the context is missing, and metaphorical definitions also lack a definition of specific properties.

In the conceptual analysis of communication models, we will focus on those components that would allow us to reach a definition of a document that meets the requirements of the classical Aristotelian definition. We will try to capture the specific differences and the context in which documents are incorporated in social communication as fully as possible using a systematic approach.

The Table 1 below summarizes the basic categories for the definition of document, which we will use as criteria in the conceptual analysis of communication models. The categories are grouped into three basic facets that cover 1) the document as a whole, 2) the components (structure) of the document, and 3) the properties of the document.

| 1. What is a document? |

Objectively (what it „really“ is) – gist, essence, substance | |

| Subjectively (as a subject perceives it) | ||

| 2. What components make up a document (structure)? | Document elements | |

| Relationship of elements in a document | ||

| 3) What are the properties of a document? | Purpose | transmision of content in space |

| transmission of content in time | ||

| access to content, content sharing | ||

| Function i.e.what (what processes) | can be done with a document | |

| can a document "do" | ||

| Attributes | of a document's content | |

| forms of a document's content | ||

| of material carrier | ||

| Relationship, i.e. context | cognitive context | |

| ontological context | ||

Tab. 1 Facets following document definition

The content of the first facet shows that it is possible to note two different options for document definition already at the basic level of understanding of a document as a system, where we perceive it holistically as a whole defined in relation to its surroundings. The objective method is based on the Aristotelian idea that it is possible to reveal the truly existing gist, substance, or essence, of a phenomenon subject to examination. The subjective method specifies a document by how it appears to an observer. This phenomenological method[1] of knowing the world through what a subject perceives and feels is concretized in the context of digital products and services as user experience. The question of which of these methods to prefer is becoming more relevant for a digital document: is its essence what the user perceives and experiences, for example, through a computer display in the form of an individually customizable user interface, or is it some digital objects, data, and programs that physically constitute it, or merely some algorithms that make it possible to create it?

The second and third facets include categories that are the result of a systemic analysis of the document. In accordance with the systematic approach, we will consider its purpose to be the most important of the document’s characteristics listed in these facets, which we will establish axiomatically as facilitating any type of indirect communication of content.

The classic system analysis procedure distinguishes between structure and function. A structural definition of document views a document as a thing (see Buckland, 2017, p. 22); it establishes what a document is, what elements (component parts) it is composed of, and what their relationships are. A functional definition views a document as a process or as an event in its life cycle. We then define the functions of the document as processes that make it possible to achieve the specified purpose. They are divided into two groups: processes or events influencing the document (what can be done with the document) and processes by which the document influences its users (what the document "does").

For the purposes of this study, we will add another dimension of analysis specific (not only) to documents – the division into content and form.[1] Such a division is based on the Platonic distinction between the material and the ideal represented by pairs of various names: matter and consciousness, soul and body, denoting and being denoted as a form and a meaning of the sign in Saussure's concept, work and expression in the IFLA LRM model, etc. Just as structure and function form a unity in reality, content and form are inextricably linked to each other. However, within the framework of system analysis, which is a logical analysis, it is possible to treat them separately and focus on specific cases of their interaction.

A content definition of document focuses on the meaning conveyed by the document (subject, topic, aboutness of the message). Form is commonly understood as the external arrangement ("appearance") of content. However, the internal components of content can also be arranged – in this aspect, form is getting closer to the concept of structure. While content is definitely abstract, form can be divided into two types – the abstract content form expressing (encoding) a message (e.g., image, motion, sound) and the concrete form or material carrier, which is a concrete physical object, on which or by which the abstract content and form are recorded, transmitted, or shared (e.g., paper, electromagnetic waves). It can be stated that content and content form defined in this matter make up the structure of the message, and the material carrier forms the infrastructure for its communication. The starting point for the categorization of document attributes will therefore be a triadic division of the document into content, content form, and material carrier.

We will examine the relationships of the document to related entities on two levels. A cognitive (gnosiological, epistemological) level allows us to define the relationship of the concept of document to the important concepts, with which it is semantically related (e.g., an information resource, a medium). An ontological context consists of the environment, in which the document exists, such as information environment (infosphere), social communication system, bibliographic universe, library, corporate information system.

2.2 Characteristics of Models

In this section, we will concentrate on how social communication is portrayed by its models. Social communication is an intensively researched area and a considerable number of models have already been created in this research. The models we considered for the analysis include the Semantic Web model[1], the Open Document Architecture (ODA) model (ISO 8613), or the popular Laswell model of social communication ("Who says what to whom and with what effect?"), the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model of cultural heritage information, the reference model of the Open Archival Information System (OAIS), or the abstract model for Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) Abstract model.

For our study, we have chosen two models of social communication that we deem most significant, developed in the mid-20th century and widely accepted and discussed outside the disciplines within which they were originally created: the Shannon-Weaver general model of communication and the Jakobson linguistic model of communication. For our needs, it is relevant that neither was created empirically, but both were derived from scientific theories. They are therefore supported by highly abstract scientific disciplines (mathematical information theory, linguistics and semiotics), which allows their applicability even in the current communication environment, which is dramatically different from the communication environment at the time of their creation.

The third selected model is the IFLA LRM reference conceptual model of bibliographic information with roots in the 1990s. Its core is a generalization of historically accumulated experience with the description of documents in the domain of memory, collection-holding and cultural institutions. It has contributed to the development of the bibliographic information theory by its multifaceted view of the document through the entities work, expression, manifestation, and item, which offers a way of resolving the document’s content-form relationship. The specificity of the model lies in its focus on the meta-level of information about these entities, metadata, rather than the "primary" entities participating in the communication process. Although it is not directly related to any of the theoretical scientific disciplines, the IFLA LRM model is currently accepted as the most important model in information science and widely applied in practice.

Each of the selected models focuses on a certain part or an aspect of social communication. The discourse universe of the Shannon-Weaver model is based on the technical aspects of communication, it is optimized for long-distance communication using technical means. Jakobson is interested in direct linguistic communication, in which he emphasizes the poetic function of language. The IFLA LRM model covers the so-called bibliographic universe[1] and focuses on communication in time, which is indirect in nature and mediated by communication media.

Nevertheless, these specifics of the individual models, which make it impossible to unify them directly, can also be seen as an advantage, allowing the application of the principle of complementarity proposed for document definition by the neo-documentalist school (see Lund 2004). Again, the aim of this study is not to evaluate the selected models, but to use the results of their analysis to construct a working document model.

2.2.1 Shannon-Weaver Model of a General Communication System

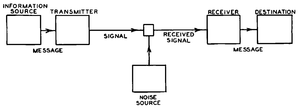

Figure 2 shows a model of a general communication system as it was presented in 1949 by its authors – American mathematicians and computer science pioneers Claude Elwood Shannon (1916–2001) and Warren Weaver (1894–1978). They developed the diagram as an illustrative aid to understand the essence of Shannon's mathematical theory of communication, which, in addition to the entities mentioned in the model, includes the commonly used concepts of information, entropy and redundancy (Shannon and Weaver 1949).

Fig. 2 Model of a general communication system (Source: Shannon and Weaver, 1949, p. 98)

The model consists of the following components and the processes implemented by them: Information source selects a message to be communicated from a set of available information.[1] According to Shannon and Weaver, the content (semantics) of a message is a matter of the context, in which the information source is located. However, this context is not shown in the diagram. A transmitter encodes a message so that it can be communicated over a transmission channel in the form of a signal. The channel (shown by a blank square in Figure 2) is a noise source and the reason why the signal received usually differs from the signal transmitted. A receiver decodes the received signal and forwards the message to a destination.

Of the three levels of communication named by the authors according to the problems solved as the level of technology, semantics and efficiency (i.e., pragmatics), the model presents the technical level only. Nevertheless, the authors indicate in the introductory remarks the ambition to capture with their model a truly general problem of communication at a machine level, and of human, social communication.

"The word communication will be used here in a very broad sense to include all of the procedures by which one mind may affect another. This, of course, involves not only written and oral speech, but also music, the pictorial arts, the theatre, the ballet, and in fact all human behavior. In some connections it maybe desirable to use a still broader definition of communication, namely, one which would include the procedures by means of which one mechanism (say automatic equipment to track an airplane and to compute its probable future positions) affects another mechanism (say a guided missile chasing this airplane). " (Shannon and Weaver, 1949, p. 95)

The aim of communication so defined is therefore not a mere passive transmission of a message, but "influence", i.e., a change in the behaviour of the recipient caused by the message. This corresponds to the generally accepted idea of two interconnected aspects of a document – a document as a report on reality and a document as a process of influencing reality.

2.2.2 Jakobson's Linguistic Model of Communication

The linguist Roman Jakobson (1896–1982) was one of the founders of the Prague Linguistic Circle and is one of the most prominent representatives of functional structuralism. The following statement can be considered a manifesto of Jakobson's systematic approach to language:

"There is no doubt that for every linguistic community, for every speaker, there is a unity of language, but this all-encompassing code is a system of interrelated subcodes; Every language contains several parallel structures, and each of them is characterized by a different function." (Jakobson, 1995, p. 77)

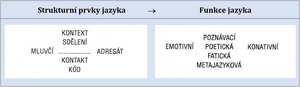

In his model of constitutive factors of a speech event (the act of verbal communication) and the associated functions of language, Jakobson combines Shannon's cybernetic approach with the semiotic approach of the Austrian psychologist Karl Bühler (1879–1963). Bühler defines three functions of the linguistic sign: in relation to objects and states of things, the representational function is manifested (German. Darstellung), in relation to the sender of the message, the sign has an expressive function (German. Ausdruck), and in relation to the recipient of the message, an appeal (challenge) function (German. Appell). (Bühler 1934) In his lecture Linguistics and Poetics at the 1958 Style in Language conference, first published in a revised version in 1960 (Jakobson 1960), Jakobson arrived at six key factors in language communication. He characterises them as follows:

"The ADDRESSER sends a MESSAGE to the ADDRESSEE. To be operative, the message requires a CONTEXT referred to ('referent' in another, somewhat ambiguous nomenclature), seizable by the addressee, and either verbal or capable of being verbalized; a CODE, fully, or at least partially, common to the addresser and the addressee (or in other words, to the coder and decoder of the message); and, finally, CONTACT, a physical channel and psychological connection between the addresser and the addressee, enabling both of them to enter and stay in communication." (quoted by Jakobson, 1995, p. 77)

Figure 3 shows that each of these structural elements is assigned a corresponding function of language. According to Jakobson, at least one function of language is manifested in each speech event, usually there are several, and usually one of them dominates.

Fig. 3 Linguistic Model of Communication (Source: Jakobson, 1995, pp. 78, 82)

The addresser is associated with an emotive function, which roughly corresponds to Bühler's expressive function. Its task is to express the speaker's state, attitude or emotions related to communication, for example by means of interjections. The term context already occurs in the Shannon-Weaver model, and is also analogous to what Bühler refers to as "objects and states of things." Jakobson assigned it a cognitive function of language, for which it also uses semiotic terms referential and denotative. Jakobson assigned the addressee a conative function, which is similar to the appellative function in the Bühler's model and affects the addressee, typically through performative speech acts (e.g., orders, incantations, or curses). As in the Shannon-Weaver model, this model also reflects the dual role of communication – to predicate something through the cognitive function and to influence something through the conative function.

The message is Jakobson's interpretation of Saussure's concept of parole (utterance); in his model, he assigned it a self-referential poetic function that seeks the meaning of the message in itself. "The set (Einstellung) toward the message as such, the focus on the message for its own sake, is the poetic function of language." (quoted by Jakobson, 1995, p. 81)

In the model, the term contact refers to the transmission channel, which is a technical condition for communication. It is associated with a phatic function that informs the speaker and the recipient that communication is actually taking place. This enriches the idea of communication with the concept of interaction and feedback. Code is a term taken from cybernetics and in Jakobson's conception it is an interpretation of Saussure's concept of langue (system of language). A metalingual function that corresponds to it in the model ensures the encoding and decoding of the message communicated.

2.2.3 IFLA LRM Conceptual Model of Bibliographic Information

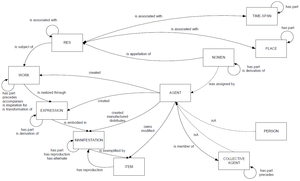

The IFLA Library Reference Model (IFLA LRM) was developed by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) and was adopted as an IFLA standard in 2017. It takes the form of an entity-relational model that consolidates the three previous models of bibliographic records (FRBR – Functional requirements for bibliographic records), name authorities (FRAD – Functional requirements for authority data) and subject authority (FRSAD – Functional requirements for subject authority data). Figure 4 shows all 11 model entities and their most important relationships, as presented in the English edition of the standard.

Fig. 4 IFLA LRM (Source: IFLA, 2017, p. 86. Available at: https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/40)

There is a generic relationship hierarchy applied in the model. Only some of the relationships are shown in Figure 4 and therefore we present their structure (the so-called backbone taxonomy) for illustration in the UML notation in Figure 5. In addition to the generic relationship hierarchy, Figure 5 also shows selected associative relationships, which are mentioned in the model’s description below.

Fig. 5 IFLA LRM backbone taxonomy

The entity res (from the Latin word for thing, LRM-E1) is at the top level of the hierarchy, comprising all entities within the universe of discourse. It fulfils a dual role: 1) it generalizes the characteristics of the entities in the model, and 2) it allows the content (subject, theme, aboutness) of a document to be expressed through the relationship of association between the instances of the entity work and res (res is subject of work / work has as subject res, LRM-R12). This addresses the relationship between a document and its content in the model.

The entity nomen (from the Latin word for name, LRM-E9) has a specific semiotic purpose in the model: it makes it possible to clearly distinguish a thing described from its designation. The relation of appellation (LRM-R13) can associate the entity nomen with any other entity, and since a relationship is defined with one-to-many cardinality, each entity can have multiple appellations.

The entity agent (LRM-E6) with subclasses person (LRM-E7) and collective agent (LRM-E8) generalizes all individual and group entities that can have any intentional relationship to bibliographic entities.

The core of the model comprises four disjoint bibliographic entities: work (LRM-E2), expression (LRM-E3), manifestation (LRM-E4), and item (LRM-E5). Each entity shows a different view of a document. A work represents the content dimension of a document, the expression represents the form of the content, and manifestation and item are entities oriented towards the dimension of a material carrier.

The model’s entity work represents the "intellectual or artistic content of a distinct creation". The adjectives "intellectual" and "artistic" convey an effort to add an artistic, cultural, emotional dimension to the understanding of the content (which Roman Jakobson would probably identify as the poetic function). Expression is defined as " intellectual or artistic content of a distinct creation". The authors of the model emphasize that they use the term "sign" in the meaning used in semiotics, i.e., as something representing something else; specifically, an expression represents a work for the user. Manifestation is understood in the model as "a set of all carriers that are assumed to share the same characteristics as to intellectual or artistic content and aspects of physical form. That set is defined by both the overall content and the production plan for its carrier or carriers". An item is an entity representing "an object or objects carrying signs intended to convey intellectual or artistic content".

The IFLA LRM model accentuates the interlinkage and interdependence of content and form of documents, with their abstract representation divided into four entities in the model, but which in fact form a whole (the content is perceived through form). The unity of content and form is modeled in several ways: by means of the relationship of the entities res and nomen linking the designated content and the designating form, by means of the relationships of realization and embodiment, and by means of a representative expression attribute.

The associative relationships of realization (work is realized through expression, LRM-R2) and embodiment (expression is embodied in manifestation, LRM-R3) interconnecting the entities work, expression, and performance, express their close connection in terms of time. "A work comes into existence simultaneously with the creation of its first expression" (IFLA, 2017, p. 21) The same applies to expression that "comes into existence simultaneously with the creation of its first manifestation" (IFLA, 2017, p. 23). In other words, "no work can exist without there being (or there having been at some point in the past) at least one expression of the work" (IFLA, 2017, p. 21) and " no expression can exist without there being (or there having been at some point in the past) at least one manifestation" (IFLA, 2017, p. 23).

A representative expression attribute (LRM-E2-A2) enables to choose from various expressions of the same work, which will be considered representational or canonical, and to incorporate its formal attributes (for example, the language in which the work was written by its author) directly into the characteristics of the work. This construction consequentially disrupts the declared disjoint relationship of entities and leads to their overlapping. The authors of the model justify this solution by the fact that even though a work is defined as content, users often identify it by its formal properties.

Unlike the two models described in the previous sections, which mention the context related to the content of the message without further specifying it, the IFLA LRM models its structure through entities place (LRM-E10) and time-span (LRM-E11), which generalize all spatial and temporal characteristics of entities in the bibliographic universe.

2.3 Conceptual Analysis of Models of Communication

This section presents concepts that have been derived from the models presented in section 2.2. The aim of the analysis is not to complete the description of the models, for the purposes of the study we selected only those concepts that we consider relevant in terms of defining the concept of document.

Although all models of communication use their own terminology, their common features are evident at the conceptual level. We tried to capture them in Table 2, in the rows of which we placed the concepts corresponding to each other. In the introductory group, concepts representing "active" human or technological elements of the communication process are presented. The following are some concepts that we have grouped together in accordance with the document definition criteria set out in Section 2.1 based on whether they refer to the content dimension of a document, the form dimension of content, or the material dimension. For IFLA LRM, some concepts are supplemented with statements that characterize their mutual relationships.

| Shannon Weaver model | Jakobson's model | IFLA LRM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information source | Addresser | Emotive function | Agent | ||

| Transmitter (encodes) | |||||

| Destination | Addressee | Connative function | |||

| Reciever (decodes) | |||||

| Message | Message | Poetic function | Work | Work is the content of a creation | content |

| Context | Cognitive function | Res | Work has subject res | ||

| Time-span | Res has temporal and spatial characteristics | ||||

| Place | |||||

| Signal | Code | Metalingual function | Expression |

Expression realizes Work Expression is a (semiotic) sign Res has appellation Nomen |

content form |

| Channel | Contact | Phatic function | Manifestation |

Manifestation embodies Expression Item exemplifies Manifestation Manifestation is a carrier of (encoded) content |

material carrier |

Tab. 2 Comparison of concepts from individual models

Of course, the comparison is based on similarity rather than equivalence; it certainly cannot be claimed that the concepts listed in one row correspond to one another fully. For example, Jakobson defines his contact not only as involving a Shannonian "physical channel", but also a "psychological connection" between the addressor and the addressee; a work from the IFLA LRM model certainly cannot be identified exclusively with the poetic function of a message conveyed through language.

For the purpose of constructing our own document model, we then synthesized the semantically corresponding concepts from the individual models. We have divided the concepts into two groups: the first includes abstract concepts (classes, so-called universals) that do not have temporal or spatial characteristics, the second includes terms that denote concrete concepts representing physical objects that exist in time and space (so-called particulars). The result comprises the seven concepts listed in Table 3.

| Abstract concepts (universals) | Concrete concepts (particulars) | |

|---|---|---|

| Content | ||

| Medium | Content form | |

| Context | ||

| Material carrier | ||

| Information source | Document | |

Tab. 3 Conceptual apparatus for creating custom document model

In order to be able to use these concepts for the construction of the document conceptual model, it is necessary to specify their meanings and mutual relations. The characteristics listed below are prepared exclusively for this purpose and are not claimed to be of general application.

In the case of the concept of content, we will stick to an intuitive understanding of its meaning, which in our model will represent what is being communicated. It corresponds to the concepts that are grouped in the category of "content" in Table 2: message in the Shannon-Weaver model, message and context in the Jakobson model, entity work together with the contextual entities res, time span and place in the IFLA LRM model.

We have chosen the abstract concept of medium as an umbrella for the concepts of signal, transmitter and receiver from the Shannon-Weaver model, code in the Jakobson model, and the entities expression, manifestation and item in the IFLA LRM model. The concept of medium is hierarchically divided into three types: abstract content form and abstract context (see the concepts of the same name in the Shannon-Weaver and Jakobson models and the concepts of time-span and place in the IFLA LRM model) and concrete material medium including the channel from the Shannon-Weaver model, contact from the Jakobson model, and manifestation and item from the IFLA LRM model.

The usual meaning given to the concept of medium is based on its etymology: something in between, in the middle, that is, a medium or an environment. In the case of communication, the medium is located between the source and the recipient of the message and enables so-called indirect communication, based not on direct contact, but on the content mediated by the medium. Together with Richard Müller and his co-authors, we will understand the medium as any means enabling the communication of content in the dialectical unity of the means and the environment (context): "It turns out that at the most general level, we can ultimately distinguish between two hardly compatible meanings of the concept of medium, which we can aptly describe as instrumental and environmental – answering the questions With what? In what?" (Müller and Chudý, 2020, p. 568) Our working definition of the concept of medium will therefore include both the material infrastructure of communication and its context, and the form that allows the content of the message to be expressed.

In accordance with the prevailing terminology, we designate a whole that is created by combining the content communicated and the medium as an information source. We therefore understand the concept of an information source as an abstract expression of the unity of content and form. The dialectical unity of the semantics of a message and its communication format is, of course, also a characteristic feature of the concept of information, which in this sense forms a pillar of the conceptual apparatus of information science. Again, the question arises whether it would not be more appropriate to denote such an abstract concept as information. In this matter, we will accept the opinion of Patrick Wilson, who, in his essay on the subject of bibliographic control, came to the conclusion that what is "controlled", or processed bibliographically, is not information as such, but an entity that he refers to as text that can (yet does not have to) be used as a source of information. He argues that the meaning that an information source acquires for the user cannot be identified with the explicit meaning of the individual statements from which it is created. "What a text says is not necessarily what it reveals or what it allows us to conclude." (Wilson, 1968, p. 18)

The specific term document, derived from the term information source, roughly corresponds to the entity of manifestation from the IFLA LRM model. We will try to define its characteristics using our own model in the following section.

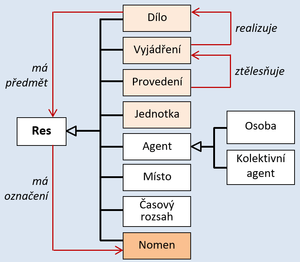

3 Document Model Design

To create our own document model, we have chosen the form of a class diagram in UML language in notation according to the ISO 24156-1 (2014) standard, which regulates the use of UML in terminological work. The structure of the model consists of classes represented by a rectangle to represent concepts, and lines or arrows to represent their relationships to each other. A relationship of association is represented by a simple line, in the case of an asymmetric relationship by a line ending with an arrow. A generic hierarchical relationship is depicted by means of an arrow ending in a triangle pointing from a child class to a parent class. A partitive hierarchy is represented by an arrow ending in a diamond, which points from class-part to class-whole.

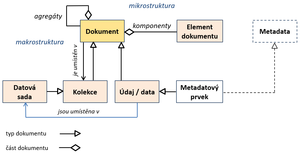

To make it easier to navigate the model, we have divided it into two parts, which are connected by the classes of document and metadata. The first part expresses the relationship of the document to other concepts, the second part of the model focuses on the granularity of documents and their typology.

3.1 Document and Its Context

The diagram in Figure 6 is divided into two levels, separated by a dotted line, in accordance with the nature of the concepts covered. In the upper part, there are abstract concepts represented by abstract classes that have no concrete instances (or their instances are concrete classes), and in the lower part there are concrete concepts (see Table 5 in Section 2.3).

Fig. 6 Relationship between document – medium – information source

The most general classes in the hierarchy indicated by the diagram are content and medium. In accordance with the working definitions we have formulated in section 2.3, we consider content to be what is communicated, and medium to be what, how, and where is communicated.

In our model, the medium class serves for a logical (and, as already mentioned, impracticable) separation of content and form of communication. The three aspects, or specific types of media, are represented by the abstract classes form, content and context, and the concrete class material carrier.

In our model, the class information source is also understood as an abstract class that has no physical instances. In the diagram, it is shown as a whole consisting of two components –content and content form, which is a specific type of medium. The relationship of association that connects the classes information source and context expresses the influence that the environment, in which it exists, has on the information resource.

In addition to the classes representing concepts derived from communication models, an abstract class metadata is added in our model. Its inclusion is motivated by the nature of the IFLA LRM model, which is also sometimes referred to as a conceptual model of bibliographic metadata. The relationship between information source and metadata is of two types. On the one hand, metadata is a specific type of information source, which is represented by the symbol of the family hierarchy, and on the other hand, it is linked to the information source by an association relationship. The associative relationship of metadata to an information source can have various semantics, the most common being the following types of relationships: 1) metadata represents a property of an information source (e.g., title, language, date of creation), and 2) metadata enables to perform operations on information sources (e.g., identify, find or select a relevant resource).

The concept of document is modeled as a specific type of information source. The generic hierarchical relationship, which connects it to the information source, allows all the properties and relationships of an information source to be transferred to the class document by inheritance. Like an information source, a document is therefore a unity of content and content form and is influenced by context. In addition, it is connected by the relationship of the partitive hierarchy with a material carrier. A document is a whole, a material carrier forms its integral part. A material carrier as such is the physical concretization of what applies to its generic concept of medium on an abstract level.

3.2 Document and Its Granularity (Macro- and Microstructures)

The diagram in Figure 7 intends to show a document no longer in relation to related concepts, but through the relationships of the whole-part hierarchy in order to present the generalized way of its (micro)structuring and incorporation of documents into larger (macro)structures. In addition, two important types of documents are added to the model – collections and data. All the concepts mentioned in this diagram are concrete, and it is assumed that they are anchored in time and space and that physical instances exist. This is also the case of the class called metadata element, which is a specification of the abstract metadata class from the previous diagram in Figure 6.

Fig. 7 Granularity of documents

The document class has two different partitive relationships represented in the diagram. The first relationship component part links a document as a whole to the class document element that represents its part. A document element can be any component smaller than the document itself and simultaneously larger than its basic building block (e.g. bit, pixel). According ISO 690 (2021, 3.7), a component part of a document is an "entity provided by a creator to form part of a host document" (for example, a name index in a book). A highly abstract and formally sophisticated system for defining document component parts is contained in the ISO/IEC 8613 standard for open document architecture . It distinguishes between the content elements, which make up the architecture of the document's content, and the elements of the document's form, distinguishing between logical and visual (layout) elements. Today, markup languages (e.g., HTML) are most commonly used to define elements of digital documents. The existence of elements in a document leads to the creation of partial relatively independent microstructures of the document, which is also perceived as a separate and integral unit of content.

The second partitive relationship of the document in our diagram is a recursive relationship called aggregates. We understand this relationship in the same way as in the IFLA LRM model, in which an aggregate is defined as a manifestation embodying multiple expressions (IFLA, 2017, p. 93). An aggregated manifestation includes (embodies) either multiple expressions of different works (e.g., in an anthology or proceedings) or multiple different expressions of the same work (e.g. in a multilingual edition). Such a division leads to the formation of macrostructures, in which it is possible to recognize several different separate units of content.

The aim of our model was not to create a comprehensive typology of documents. However, we consider it useful to display two important types of documents in the model – collections and data, and to clarify their relationship to the concept of document. A collection is a set of organized, discrete documents. In the IFLA LRM terminology, it is a set of items for which various designations are used in practice, e.g., collection, stock, set, corpus, database, repository. In the ISO 690 (2021, 3.6) standard, it is defined as " any set of one or more information resources, assembled on the basis of some common characteristic, for some purpose, or as the result of some process". Despite the intuitive notion of a collection as a whole and documents as its parts, the relationship between a document and a collection is not defined in our model as an aggregation relationship (a collection is not an aggregate), but as an association relationship — a document is placed in a collection. At the same time, as Jonathan Furner (2016, pp. 299–303) and Michael Buckland (2017, pp. 48–49) have made clear, a collection can be viewed as a document. This fact is expressed in the diagram by the generic relationship of the hierarchy between the mentioned classes – a collection is a specific type of document. Thus, the document-collection relationship is another case of indirect recursion in our model.

The concept of data is currently very frequently used, and because the volume of data communication in society grows constantly, it is sometimes perceived as an equivalent to the concept of document. A relatively widespread idea is again the intuitive idea of a document as a whole composed of data. In our model, however, data is understood as a specific type of document, i.e., content, form and material carrier are attributed to data. The class dataset in our model presents a specific type of collection in which a set of organized data is located. A metadata element is a specific type of data that has a form shared with data. At the same time, a metadata element is a specific type of metadata, to which it is also linked by a generic hierarchy relationship. Thanks to this polyhierarchy, it is possible for metadata elements to share general data properties and simultaneously an association relationship of metadata with information sources or documents.

3.3 Verification of Model’s Applicability

A modeling method usually includes a phase of testing a model being designed. In addition to logical accuracy, the applicability of the model for a practical purpose for which it was created is also verified. In the case of our working document model, we decided to corroborate whether it allows to represent specific categories of documents currently used in the cataloguing practice of libraries. For such testing, typologies contained in the controlled vocabularies of two international standards for document description – ISBD (International Standard Bibliographic Description) and RDA (Resources Description and Access) – were used, which are conceptually based on the IFLA LRM model.

When designing a typology in a class diagram (i.e., a list of subclasses of a class), it is important to clearly define a criterion of division, most often based on a suitable attribute of a class under segmentation. Because a class can have more such attributes, it is also possible to create multiple typologies for one class. A technical solution then consists in adding attributes to the appropriate classes in the model; for these attributes, it is then possible to develop value vocabularies to denote specific types. To test our model, we have chosen document typologies based on their formal attributes. These are represented in the model by the abstract class Content Form and the concrete class Material Carrier.

In the two commonly applied classification criteria for categorizing the forms of content, it is possible to distinguish an objective and a subjective method of document definition, which we have characterized in Section 2.1: objective categorization is based on the type of signs that express content (e.g., data set, text), subjective categorization is focused on human senses by which signs are perceived (hearing, taste, smell, touch, vision). Specific document typologies based on the semiotic systems used to express content include the ISBD content form value vocabulary and the RDA content type value vocabulary . The typology of documents according to the human senses for content perception is available in the value vocabulary for ISBD content qualification of sensory specification .

Various criteria can also be used for the typology of material carriers. In addition to the usual "objective" typology of materials and objects that form the physical basis of medium (e.g., audio cassette, microfiche, volume), it is also possible to encounter a typology of means or devices, through which the content on a medium is accessible to the user (e.g., a computer, microscope). A division according to type of recording capturing the dichotomy of analogue and digital documents is important.

The existing typology of documents according to their carriers is contained in RDA carrier type value vocabulary . Document typology according to the devices needed to access their content is provided by ISBD media type value vocabulary and RDA media type value vocabulary . Capturing the division into analogue and digital documents is enabled by the RDA type of recording value vocabulary . Table 4 shows how to solve the representation of document types in the model. The second column of the content form and tangible medium classes is supplemented with the relevant attributes expressing the breakdown criterion, and the third column contains examples of real controlled vocabularies, the values of which can be used to fill in the attributes.

| Model class | Attribute | Value vocabulary for attributes |

|---|---|---|

| content form |

Signs for content expression |

ISBD content form RDA content type |

| Human senses for content perception |

Content qualification of the ISBD sensory specification |

|

| Material carrier | Carrier | RDA carrier type |

| Device |

ISBD medium type RDA medium type |

|

| Recording method |

RDA type of recording |

Table 4 Typology of forms, contents and material carriers

Of course, the testing carried out cannot be considered exhaustive, but for this small sample, it has confirmed that the designed document model is compatible with the tools for description and typology of documents based on their format, which are common in practice.

4. Summary: Towards a Functional Definition of Document

The document model presented in this study is static, focusing exclusively on the elements and their mutual relationships. The next step towards a systematic view of the document must therefore be to define the functions and assign them to the appropriate model components. The statement addressed to media can apparently be applied to the document: "Consideration of processes [...] would then open the way to the most general description of mediality as something shared by all media [...] Therefore, capturing operations or processes related to media is crucial." (Müller and Chudý, 2020, p. 570) We believe that the functions defined in these models could serve as a basis for conceptual analysis and subsequent transformation of the existing models, in the same way as a static model of a document may be derived from analysing models of communication. A preliminary overview of potentially relevant functions is provided in Table 5.

| Shannon-Weaver model | Jacobson's model | Model IFLA LRM |

|---|---|---|

|

Select message Encode message Transmit signal Decode signal Noise (content distortion) |

Emotive function Connative function Poetic function Cognitive function Metalingual function Phatic function |

Find document Identify document Select document Obtain document Explore, discover document |

Table 5 Document functions in communication models

So far, the overview of functions has taken the form of simple lists, the designation of individual functions is taken verbatim from individual models, and no steps have been taken to compare them. This will require a thorough analysis. It is evident that each set of functions aims at a different dimension of a document: In the Shannon-Weaver model, the functions focus on the communication process itself, the Jakobson model captures the effect that a message communicated has on its recipient, and the IFLA LRM model prescriptively postulates functions that metadata is supposed to fulfil in relation to a document. The model is limited to bibliographic metadata functions corresponding to the requirements of end users and does not include any functions associated with administrative, management or copyright-related work of libraries.

Perhaps a pair of bibliographic control tasks as described by Patrick Wilson could be a unifying platform for looking at these variously defined functions– to describe and to use a document (Wilson, 1968, p. 20), in combination with the three functions of media defined by the media theorist Friedrich Kittler as transmission, preservation and processing of information (Kittler, 1993, p. 8). Further initiatives could be expected from the theory of document acts (Smith, 2012).

Conclusion

This study has aimed to verify the applicability of conceptual analysis of reference models of social communication to the construction of a conceptual document model. That objective has been met by demonstrating that the communication models chosen provide a relevant conceptual basis applicable to that purpose. In addition to the concepts derived from the models using the method of conceptual analysis, the characteristics of their mutual relations in the individual models have also proven to be useful. Given that the models used for the analysis are embedded in a number of theoretical disciplines, this study can also be considered as a contribution to the interdisciplinary interconnection of information science with other scientific disciplines.

The follow-up sub-objective was to use the results of the analysis of the three selected models of communication to construct a conceptual model of the document. The use of the method of model creation and the technique of graphical modeling in the form of a UML class diagram made it possible to approach this task in an illustrative manner that clearly and unambiguously expresses the semantics of the model’s components, including their mutual relations. As the partial probe focused on formal document typologies has shown, the draft model is also ready to test usability for the representation of specific document instances or their partial aspects.

We see the specific contribution of the designed model to the development of document theory in three main areas: 1) a draft solution to the relationship between the concept of document and the related concepts of information, medium, and information source, 2) a draft general method of modeling document granularity, and 3) a draft general method of modeling document typology.

We believe that this study has shown that the method of conceptual analysis and conceptual modeling is a relevant method for the document theory. The first steps in this direction, which we have taken and presented in this paper, can be considered a sort of a preliminary probe into the issue. There are certainly some alternatives to the solutions we have adopted during the conceptual analysis and model construction, which would be appropriate to discuss in a broader research community. Nevertheless, in its current provisional form, they indicate that this method could bring useful results in the future. We can see further possibilities for continuing in this direction, especially when focusing on the functional aspects of a document.

Literature

BEARD, David, 2008. From work to text to document. In Archival science. September 2008, 8(3), 217–226. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-009-9083-4. ISSN 1389-0166 (print). ISSN 1573-7500 (online).

BUCKLAND, Michael Keeble, 2017. Information and society. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 217 p. ISBN 978-0-262-53338-6.

BÜHLER, Karl, 1934. Sprachtheorie: die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Jena: G. Fischer. xvi, 434 p.

FURNER, Jonathan, 2016. „Data“: the data. In: Matthew Kelly a Jared Bielby, ed. Information cultures in the digital age: a festschrift in honor of Rafael Capurro. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 287–306. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-14681-8_17. ISBN 978-3-658-14679-5 (print). ISBN 978-3-658-14681-8 (online).

GLUSHKO, Robert J., 2016. The concept of „resource“. In Robert J. Glushko, ed. The discipline of organizing: professional edition [online]. 4th ed. O'Reilly Media, chapter 1.3, pp. 36–38. Available at: https://ischools.org/resources/Documents/Discipline%20of%20organizing/Professional/TDO4-Prof-CC-Chapter1.pdf [accessed 2022-09-21].

IFLA, 2017. IFLA library reference model: a conceptual model for bibliographic information [online]. Pat Riva, Patrick LeBoeuf, Maja Žumer, ed. Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, rev. August 2017 as amended and corrected through December 2017 [accessed 2022-09-21]. 101 p. Available at: https://www.ifla.org/publications/node/11412.

ISO 690, 2021. Information and documentation – Guidelines for bibliographic references and citations to information resources. 4th ed. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization, 2021-06. ix, 160 p.

ISO 24156-1, 2014. Graphic notations for concept modelling in terminology work and its relationship with UML – Part 1: Guidelines for using UML notation in terminology work. 1st ed. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization, 2014-10. 24 p.

JAKOBSON, Roman, 1960. Linguistics and poetics. In Style in language. Thomas Albert Sebeok, ed. Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press, s. 350–377. – In Czech: JAKOBSON, Roman, 1995. Lingvistika a poetika. In: Poetická funkce. Miroslav Červenka, ed. Vyd. tohoto souboru 1. Jinočany: H & H, pp. 74–105. ISBN 80-85787-83-0.

KITTLER, Friedrich Adolf, 1993. Draculas Vermächtnis: Technische Schriften. Leipzig: Reclam. 259 p.

KUČEROVÁ, Helena, 2017. Sémantická problematika organizace znalostí. In Organizace znalostí: klíčová témata. Praha: Karolinum, pp. 201–230. ISBN 978-80-246-3587-3 (paperback). ISBN 978-80-246-3597-2 (pdf).

KUČEROVÁ, Helena, 2018. Pojem modelu a pojmový model v informační vědě. In Knihovna: knihovnická revue. 29(2), 5–32. ISSN 1801-3252 (print). ISSN 1802-8772 (online).

KUČEROVÁ, Helena, 2021. Teorie dokumentu: od antilopy k informační architektuře. In Knihovna: knihovnická revue. 32(2), 5–34. ISSN 1801-3252 (print). ISSN 1802-8772 (online).

LUND, Niels Windfeld, 2004. Documentation in a complementary perspective. In: Warden Boyd Rayward, ed. Aware and responsible: Papers of the Nordic-International Colloquium on Social and Cultural Awareness and Responsibility in Library, Information and Documentation Studies (SCARLID). Oxford: Scarecrow Press, pp. 93–102. ISBN 0-8108-4954-2.

LUND, Niels Windfeld, 2010. Document, text and medium: concepts, theories, and disciplines. In Journal of documentation. September 2010, 66(5), 734–749. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411011066817. ISSN 0022-0418.

MÜLLER, Richard, Tomáš CHUDÝ a kol., 2020. Za obrysy média: literatura a medialita. Praha: Ústav pro českou literaturu AV ČR: Karolinum. 665 p. ISBN 978-80-246-4688-6 (Karolinum). ISBN 978-80-7658-005-3 (Ústav pro českou literaturu AV ČR).

OTLET, Paul. Traité de documentation: le livre sur le livre, théorie et pratique, 1934. Bruxelles: Editions Mundaneum. 431 p.

RANGANATHAN, Shiyali Ramamrita, 1931. The five laws of library science. Madras: The Madras Library Association; London: Edward Goldston. 458 p.

SHANNON, Claude Elwood a Warren WEAVER, 1949. The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1949. 125 p.

SMITH, Barry, 2012. How to do things with documents. In: Rivista di estetica. 50, 179–198. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4000/estetica.1480. ISSN 0035-6212 (print). ISSN 2421-5864 (online).

STODOLA, Jiří, 2020. Ontologický a sémantický status díla: impulzy literární vědy k promýšlení standardní knihovnické ontologie. In: Knihovna: knihovnická revue. 31(2), 29–44. ISSN 1801-3252 (print). ISSN 1802-8772 (online).

VODIČKOVÁ, Hana, 2007. Malá úvaha o české knihovnické terminologii v souvislosti s novými „pařížskými principy“ pro katalogizační pravidla aneb o FRBR. In Čtenář. 2007, 59(1), 4–8.

WILSON, Patrick, 1968. Two kinds of power: an essay on bibliographical control. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987, © 1968. 155 p. California library reprint series. ISBN 978-0-520-03515-7.

Notes

1 Note: Definition of the term information is outside the scope of this paper. Please note that when we use the term information in this text, we mean organised meaningful data.

2 For example, see the definition of a document in the terminology standard ISO 5127:2017 (3.1.1.38) and in the ISO 690 standard (2021, 3.13): 'recorded information or a material object, which can be treated as a unit of the documentation process'.

3 Note: For those interested in a more detailed explanation, see Patrick Wilson’s essay (1968, pp. 15–19).

4 Note: The phenomenological approach is also the basis of the diachronic (historical) view of the document, which deals with the question at what stage of its life cycle an object examined was considered a document (Buckland, 2017, pp. 23–24).

5 Note: As we will see below, the dimensions of structure-function and content-form are not completely disjoint, which applies at least to the categories of form and structure.

6 See "semantic web layer cake" on the https://www.w3.org/2007/03/layerCake.png or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_Web_Stack.

7 Note: The term "bibliographic universe" is not understood uniformly. Most often, it is identified with a set of bibliographic entities (in the IFLA LRM model, these are represented by the entities work, expression, manifestation, and item). Sometimes, however, the entire IFLA LRM model itself is referred to as a model of the bibliographic universe (IFLA, 2017, p. 5). For the purposes of our study, we will use the term bibliographic universe in its first meaning, i.e., as a set of bibliographic entities. It would therefore be more accurate to say that the IFLA LRM model covers the bibliographic universe and its directly related entities.

8 Note: The difference between information and message plays an important role in this model. The authors clearly declare that what is communicated is not information, but news (Shannon and Weaver, 1949, pp. 99–100).

9 Note: Similarly, we can observe overlapping levels of technique, semantics and effectiveness of communication in Shannon-Weaver's model. Jakobson's functions of the linguistic sign are also not considered to be strictly disjoint and are present to varying degrees in every linguistic act.

10 We deal with the issue of content in more detail in (Kučerová 2017). The semiotic and semantic aspects of document are also dealt with by Jiří Stodola (Stodola 2020).

11 Note: Although we preferred the term content to the term information in our study, we do not consider it appropriate to introduce the neologism "content source".

12 Note: The relationship between indirect recursion of metadata and information source is not unusual, in language communication the relationship metalanguage – object language is considered in a similar way.

13 ISO/IEC 8613-1, 1994. Information technology – Open Document Architecture (ODA) and interchange format: Introduction and general principles – Part 1. 1. ed. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization, 1994-12. 77 p.

14 IFLA. ISBD Content Form [online]. Available at: http://iflastandards.info/ns/isbd/terms/contentform.

15 RDA Content Type [online]. Available at: https://www.rdaregistry.info/termList/RDAContentType/.

16 IFLA. ISBD Content Qualification of Sensory Specification [online]. Available at: http://iflastandards.info/ns/isbd/terms/contentqualification/sensoryspecfication.

17 RDA Carrier Type [online]. Available at: https://www.rdaregistry.info/termList/RDACarrierType/.

18 IFLA. ISBD media type [online]. Available at: http://iflastandards.info/ns/isbd/terms/mediatype.

19 RDA media type [online]. Available at: https://www.rdaregistry.info/termList/RDAMediaType/.

20 RDA type of recording [online]. Available at: https://www.rdaregistry.info/termList/typeRec/.

KUČEROVÁ, Helena. Teorie dokumentu a modely komunikace. Knihovna: knihovnická revue. 2022, 33(2). ISSN 1801-3252.