Riches of Old Maps and Their Utilisation by Libraries and Other Memory Keepers

Keywords: old maps, old globes, old atlases, map digitisation, globe digitisation, map collections

Ing. Milan Talich, Ph.D. / Výzkumný ústav geodetický, topografický a kartografický, v.v.i. (Research Institute of Geodesy, Topography and Cartography, v.v.i.), Ústecká 98, 250 66 Zdiby

- 1. Introduction

Libraries, as well as archives, museums and other memory institutions, should provide access to books as well as to other documents. In addition to magazines, newspapers, photographs or music media (to name a few), these documents also comprise cartographic works - maps, including multi-sheet map series, atlases and globes. At the same time, libraries should provide for the interconnection between the paper and digital worlds of documents. And it is not enough for libraries to only lend these documents; other services are needed for their survival and future development. Libraries thus play a role of information, community and especially educational institutions.

However, education and literacy skills also include the “ability to read a map”. It means learning to see things in a spatial context, which is essential for the ability to structure events, information and knowledge in terms of space and position - and then to make decisions with the support of spatial information. This skill is not innate and it needs to be learned from childhood on. A map is an essential tool in this learning process. Those who do not learn this skill are less well versed in spatial contexts and can therefore be expected to be less successful in life. Moreover, old maps add another dimension to this ability - an awareness of development and time contexts.

Today’s readers want the required documents right away - as soon as possible and preferably from the comfort of their homes. Moreover, when it comes to (old) maps typical readers do not know which particular map to ask for. They usually come with a request such as “I want a map from a certain region, with a certain detail resolution and from a certain time period”. How to meet such a requirement if the library owns thousands or tens of thousands of old maps? The solution comes in the form of specialised search services for quick finding of relevant maps according to the above criteria. However, this requires not only their cataloguing including the specific data needed, but also digitisation and access to the digitised format. However, mere digitisation and subsequent free online access to view old maps is no longer enough for readers-users. They want to preserve and make full use of the potential of old maps, i.e. cartographic works, with all their specific properties - for example for measuring lengths, directions, areas, etc. And that is not all. User requirements are increasing; users are asking for some kind of added value to make their work with digitised old maps easier and, in particular, to obtain more information than is possible with the traditional use of paper maps. Digitisation, which in the mid-1990s was seen only as a tool for protecting resources and making them available, is now turning into a new service tool for readers - map users.

Old maps, plans, map atlases as well as globes are undoubtedly part of our cultural heritage. They are part of our history, visually depicting the situation at the time of their creation and complementing other historical sources. They are also important evidence of the skill, state of knowledge and artistic maturity of our ancestors.

Due to the process of their creation, maps are, unlike other historical documents, unique works. From a cartographic perspective, the oldest maps (among them also pictorial relief maps) are considered pictures or sketches rather than real maps. However, from the beginning of the 18th century, some maps started to be made on the basis of accurate geodetic measurements as well as mathematically defined map projections. Such maps could thus be used to accurately measure lengths, determine directions and calculate surface (area). It should be noted that each map has its own positional accuracy, which is based on the mapping method, instrumentation and map scale used. Maps, plans and globes are therefore works that have their cartographic properties - and only if we know these properties and, more importantly, preserve them during digitisation, we can make a full use of their information potential. At the same time, we should bear in mind how much efforts were required to create every single map with the above cartographic properties. Hundreds to thousands of people participated in their creation as it was at first necessary to address complex theoretical issues of how to project the Earth’s surface in the map plane (paper), how to build the necessary geodetic bases using measurements and calculations, including geodetic point fields (thousands of trigonometric and levelling points in the Czech Republic), perform own detailed mapping by field surveys and finally draw a map at the required scale, i.e. to make the final product. A failure to respect the cartographic properties and positional accuracy of a map during its digitisation and online projection turns such a map into a mere pretty picture and all the efforts made by our ancestors as described above are wasted.

There is no need to emphasise the need to digitise and make available archival materials, including maps. Researchers demand convenient and fast access to information. This paper should provide staff of memory institutions, especially libraries, with clear information on how to help readers find and use old maps, and advise what principles to follow when digitising their own map collections. At first, you will find an overview of major map collections in the Czech Republic with a special focus on the Chartae-Antiquae.cz Virtual Map Collection1.

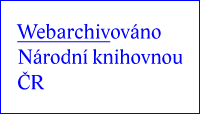

Fig. 1 A section of a manuscript map of the town of Hlinsko dating back to 1731, State Regional Archive in Zámrsk. Available at http://www.chartae-antiquae.cz/maps/19248

- 2. Map Collections and the State of their Digitisation

The most extensive map collection in the Czech Republic is the collection of the Central Archive of Surveying and Cadastre (ÚAZK), which amounts to over 500,000 map sheets. The archive houses a rich collection of cadastral maps, other large map series, as well as a collection of various old maps, plans, atlases and globes. The most valuable and at the same time the most frequently used map resource is the “Stable Cadastre, Its Maintenance and Renewal (1824–1955)”, which consists of:

- The so-called Imperial Obligatory Imprints - coloured copies of the original maps of the stable cadastre, originally intended for archiving in the Central Archive of Cadastre of Lands in Vienna, show the original state of the landscape at the time of their creation, i.e. between 1824 and 1843, without drawings of later changes;

- Original maps - are a direct output of surveying work at the time when the stable cadastre was established. These are hand-drawn and coloured maps, which were lithographically reproduced after their completion. Always one of the printed copies (after it had been hand-painted) was stored in Vienna as a control specimen, so-called imperial obligatory imprint. The changes made during map revision surveys (updates) in the years 1869 to 1881 were later plotted in the original maps in red;

- Indication sketches - coloured copies of a map sheet divided into quarters and glued to hard paper. The purpose was to check in the field and supplement information from the field sketches during cadastral mapping so that the map sheets could be completed and parcel records drawn-up in winter. The signatures of the mayor and municipality representatives on the back of indication sketches confirm their consent with the facts established during field tours;

- Map revision surveys of the stable cadastre - a failure to introduce changes to the stable cadastre gradually resulted in its mismatch with reality. Therefore, the Act “On the Revision of the Land Tax Cadastre” was adopted on 24 May 1869, which triggered the process of map revision surveys - change mapping. Map revision surveys took place between 1869 and 1881 and were drawn in the original maps. From 1883, on the basis of a new Act of 23 May 1883 “On the Maintenance of the Land Tax Cadastre in the Register”, the so-called “updated maps of the stable cadastre”, sometimes also called “cadastral correction sheets 1: 2 880” were created, which contained drawings of further changes.

However, it should be noted that indication sketches are not part of these resources of ÚAZK as they are physically stored in the National Archive in Prague (for Bohemia), in the Moravian Regional Archive in Brno (for Moravia) and in the Regional Archive in Opava (for Silesia). They are therefore part of the relevant holdings of these archives, while their data (raster images) are available for viewing on the ÚAZK website on the basis of mutual inter-archive agreements. ÚAZK continuously digitises their map resources and makes maps available at archivnimapy.cuzk.cz. This is where you can find imperial obligatory imprints, original maps of the stable cadastre, indication sketches, maps from the 3rd Military Survey, topographic maps in the S-1952 coordinate system, all successive editions of the State Map derived 1 : 5,000 (SMO-5), maps of real estate records as well as maps and plans from the collection until 1850. The holdings therefore consist mainly of large multi-sheet map series. The digitisation of the entire map collection should be completed by the end of 2020.

Another large map collection is owned by the Military Geographic and Hydro-meteorological Institute of General Josef Churavý (VGHMÚř). There are about 150,000 mainly military maps in the collection, which consists predominantly of special-purpose and general maps from the 3rd Military Survey, Czechoslovak military maps as well as nationality and tourist maps. Some sheets are archived in several copies.

In addition to the collection of maps, VGHMÚř also keeps around 730,000 negatives of aerial survey images (ASI) (1936–2010). The digitisation of old military maps is not carried out at VGHMÚř. Historical ASIs are systematically digitised in cooperation with VGHMÚř and the Surveying Office and published in the application called “National Archive of Aerial Survey Images” at https://lms.cuzk.cz/lms/lms_prehl_05.html. It is also possible to order a copy of historical aerial survey images from a period of 1937 to 2002 for a fee at http://www.geoservice.army.cz/historicke-lms.

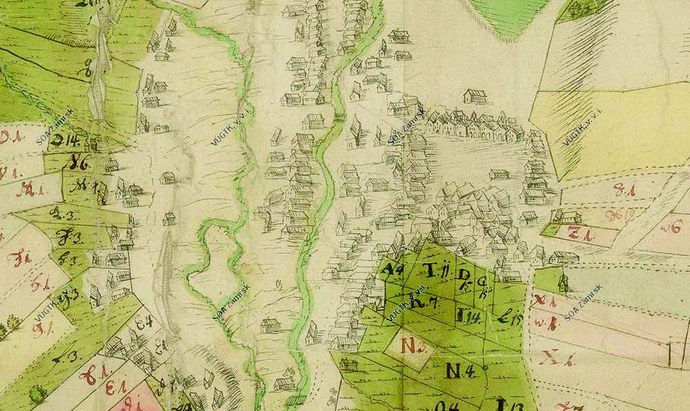

Fig. 2 Archive of aerial images of Prague at http://app.iprpraha.cz/apl/app/ortofoto-archiv/

In addition, aerial images of various towns and cities from various time periods can be found on the Internet, such as of the capital city of Prague (http://app.iprpraha.cz/apl/app/ortofoto-archiv/), the city of Pilsen (http://gis.plzen.eu/staremapy/), or the city of Karviná (http://uap.karvina.cz/) and the town of Klecany (https://maps.cleerio.cz/klecany). For example, the Cenia map portal has made available an orthophotomap of the entire territory of the Czech Republic from the 1950s (http://kontaminace.cenia.cz/). A historical orthophotomap of the entire territory of Slovakia is available on the map portal of the Technical University in Zvolen (http://mapy.tuzvo.sk/HOFM/).

The Map Collection of the Faculty of Science of Charles University amounts to ca 130,000 maps, 2,000 atlases and 80 globes (http://www.mapovasbirka.cz/). Digitisation is currently underway and around 65,000 documents are available in the electronic catalogue.

Another collection is the Map Collection of the Institute of Geography of Masaryk University in Brno, though not so extensive. It has approximately 18,000 inventory items that are continuously digitised (http://mapy.geogr.muni.cz). Moll’s Map Collection of the Moravian Regional Library in Brno with 12,000 maps, available in a digital format at http://mapy.mzk.cz/ , ranks among minor map collections. The collection of the National Technical Museum amounts to a similar number of about 20,000 maps.

Thousands to tens of thousands of maps can be found in the holdings of individual State Regional Archives, and hundreds or thousands are also preserved in each of their subordinate district archives. In total, the state archives may hold about 300,000 old maps.

Major map collections include the Map Collection of the Institute of History of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague City Archives, the National Library of the Czech Republic with its Lobkowicz Collection, and the National Archive in Prague. Old maps can also be found in city museums, scientific, castle and other libraries as well as in heritage institutes.

In the above institutions, the digitisation of maps is carried out using different procedures and different instrumentation. There are also various other methods, software or web applications, to make maps available online, though these provide the user with a not always satisfactory image quality and often limited interactivity. In many cases, the user does not have the opportunity to use all the information potential that is hidden in maps. Therefore, the project titled “Cartographic Sources as Cultural Heritage”, described in more detail in the next chapter, has been implemented. Its ambition has been to show how to properly digitise and make cartographic works accessible to provide the user with appropriate conditions and tools for the maximum utilisation of old maps, including for their own projects. The project also aims at creating and offering the necessary methodologies, technologies and SW tools.

- 2.1 Cartographic Sources as Cultural Heritage

The full name of the project is “Cartographic Sources as Cultural Heritage. Research into New Methodologies and Technologies for Digitisation and Utilisation of Old Maps, Plans, Atlases and Globes.” The project was funded by the NAKI (National and Cultural Identity) Programme of the Ministry of Culture for 2011–2015. Two research institutions collaborated on the project, namely: The Research Institute of Geodesy, Topography and Cartography, v. v. i. (VÚGTK) and The Institute of History of the Czech Academy of Sciences, v. v. i. (HÚ AV ČR) 2.

The name of the project suggests that the solution lies in new methodologies and technologies that make old maps accessible in the Internet environment. The tangible output of this five-year project is (and that is certainly the most interesting for the users) a number of freely available web applications that increase the efficiency of working with old maps. At the same time, a database of digital old maps has come into light. These maps were scanned as part of the project. The map database and web applications are available free of charge at Chartae-antiquae.cz or at a simpler address virtualnimapovasbirka.cz.

The project has gradually been joined by a number of institutions which house map collections that have not yet been systematically digitised. It is worth noting that these are both nationwide institutions and small institutions with only a local reach. They include various state regional and district archives such as the National Archive, various museums including the National Technical Museum, libraries such as the National Library in Prague, the Moravian Regional Library in Brno or the Municipal Library in Prague, church institutions (The Royal Canonry of the Premonstratensian Order in Strahov) as well as private collectors and antiquarians specialising in old maps. All the institutions signed cooperation agreements that also covered reproduction rights to digitised cartographic works and providing their digital copies to third parties.

The project results comprised of various certified methodologies, proven technologies and specialised software are available on the project website at naki.vugtk.cz, where you can also read published articles. Perhaps the most important project output for old cartographic works end users (even though from the project perspective this output might seem rather insignificant) is the Chartae-Antiquae.cz Virtual Map Collection3. This map collection will further be used as a good practice example.

2.2 Chartae-Antiquae.cz Virtual Map Collection

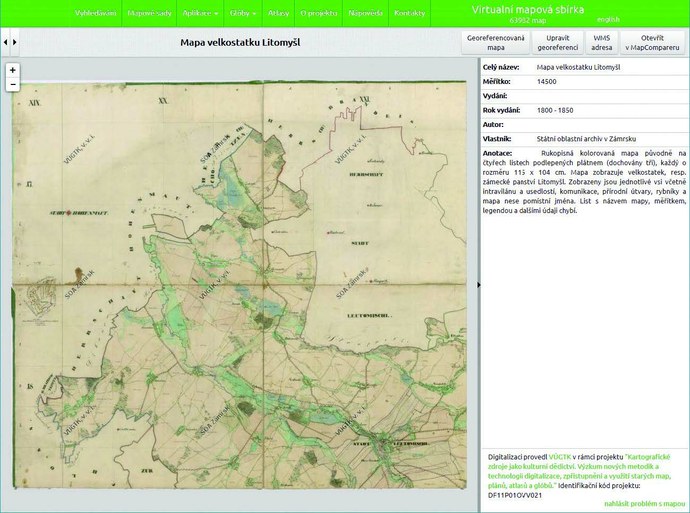

As part of the above mentioned project “Cartographic Sources as Cultural Heritage” a new web portal called Chartae-Antiquae.cz dedicated to old cartographic products has been created. The portal makes available high-resolution old maps, plans, atlases and globes from various map collections from all over the Czech Republic. There are large-scale maps, such as maps of manor farm estates, forest maps, stable cadastre maps or city plans; medium-scale maps such as maps of regions, mountain ranges or tourist maps; and small-scale maps, i.e. maps of states, continents and the world. Approximately 65,000 map sheets are now available in the database, and more maps are gradually being added. More than 75,000 old maps from the above-mentioned institutions have been scanned. The user will find some brief information on each map. A comprehensive and online accessible virtual map collection, one of the largest in the Czech Republic, has thus been created. By making maps available on the map server, via Web Map Services (WMS4 or TMS5) or various web applications, the users have been provided with new tools for analysing old maps. Special attention is paid to providing maps of the 3rd Military Survey via WMS/TMS. For this purpose, it was necessary to perform their georeferencing (placement in the coordinate system) using a special procedure, which required a mathematical derivation of a new type of elastic coordinate transformation using the collocation method (see footnotes 6, 7)6, 7. In addition to the above maps, the collection also provides access to 150 old atlases and 114 virtual 3D models of globes, which can be projected into a 2D plane.

The portal with its maps is gradually becoming an important source of information used by historians, cartographers, surveyors, landscapers, environmentalists, water managers, urban planners, architects, students, as well as researchers, the general public and lovers of old maps. It is important to note that the maps come from various map collections in the Czech Republic, of which the vast majority do not - and in the near future will not - have the funds to digitise them. Furthermore, they are very often large-scale maps (very detailed), which can be used for detailed studying of landscape transformation, population settlement, urban planning, road and water network development, etc. These detailed maps, which come abundantly from state regional and district archives, are often not found in any other memory institutions and their content is therefore unique to users.

The number of visitors to the portal accounts for about 100 to 120 thousand sessions per year, the portal has currently about 160 thousand users of which about 32 thousand return to its website regularly. About 30% of visits are from the Czech Republic, the rest from abroad.

3. Access to Digitised Old Cartographic Works

- A properly digitised old map offers a much wider use than its source paper template. It depends on the technology used to make the maps available on the Internet and the web applications and tools provided to users. In order to choose the appropriate method to make old maps available and to design tools for working with them, it is necessary to consider the following:

- What is the easiest way to find the right map?

- How best to present the maps to researchers-users on the Internet in order to use their full information potential?

- What information do users need to find on maps for their work?

-

Why do researchers use old maps and what do they want to do with them?

A careful consideration of answers will result in designing several web applications, which can be described using the below mentioned ones taken from the Chartae-Antiquae.cz portal. These reflect the most common readers’ demands for an advanced sophisticated way of working with digitised maps. For more information on trends in reader demands, see footnote 8 8.

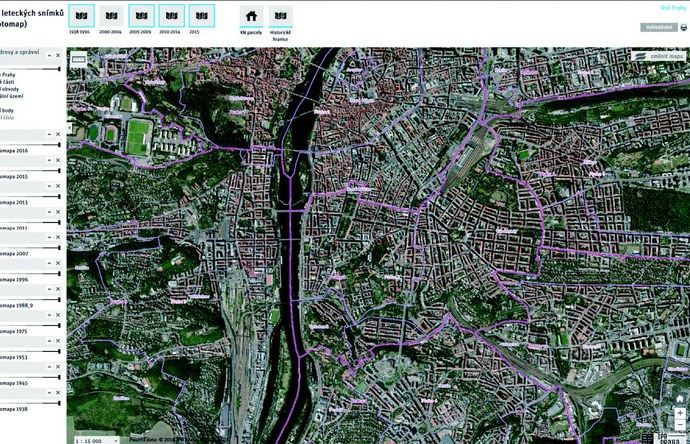

- 3.1 Geographic Search with Map Viewing

The users need to be able to navigate through the database comprising thousands of scanned maps and to find the one that interests them. Traditionally, a library database can be searched by keywords (map author, year of publication, title, etc.). If the user does not know any keyword or is interested in maps from a certain locality, the library database will not help them much. Therefore, we have a geographic search. Even though the users can enter the name of a town or village, and/or coordinates of the place they want to see on the old map in the search field, they mainly enter the following three basic parameters:

- the locality of interest - in the window of the current guide map

the range of the years of publication of the respective old maps

the range of scales for the respective old maps.

The result of the search is a list of maps found, including previews, metadata and links to view the relevant full-resolution map in the Zoomify format, i.e. a raster image of the map. The application for viewing raster images of maps then allows you to quickly scroll and zoom-in the maps in the map web browser to the tiniest detail. This is something the user will certainly appreciate, especially when it comes to large-sized maps.

Fig. 3 A geographic search for maps in the vicinity of Pardubice with the indication of the year of publication (1450–1899) and map scale limitation to 1 : 200,000

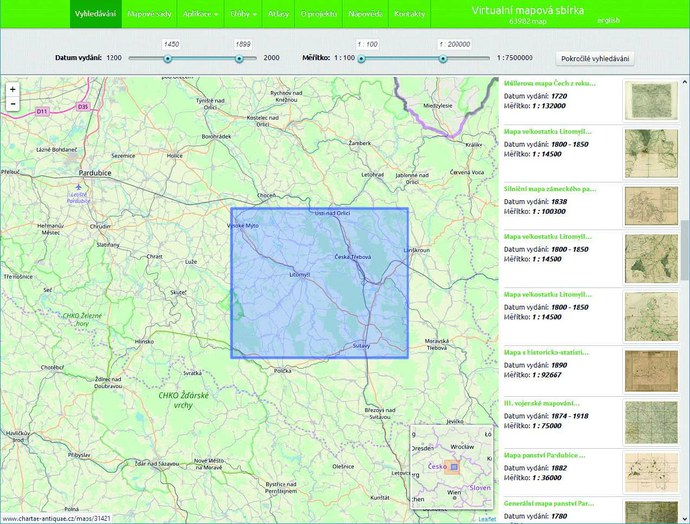

- 3.2 Access to Georeferenced Maps Using a Map Server

However, more demanding researchers demand such access to maps that enables use of their cartographic properties. This requires that the digitised raster images of old maps be georeferenced, i.e. placed in the current coordinate system, taking into account their cartographic projection. Georeferencing is a relatively complex task as each map needs an individual approach, and proper and accurate georeferencing requires knowledge of mathematical cartography and respect for the cartographic projection of the old map concerned.

Georeferenced maps are published on the Chartae-Antiquae.cz portal according to the Web Map Service (WMS)9 or Tile Map Service (TMS)10 standards administered by the OGS (Open Geospatial Consortium )11. The use of standards guarantees that all users can display the maps in desktop GIS software or in their own web applications and to tile them together or, more precisely, view them as overlays on other map layers that are also provided in the WMS/TMS format, including by another party.

If the respective map found on the portal is georeferenced, it can be displayed directly on the portal in the georeferenced map viewer. This viewing can be done together with other maps, including their simple comparison by making the layers transparent. It is also possible to copy the link for providing the relevant map in the WMS format for use in the user’s GIS or in other web applications.

Fig. 4 Viewing the found map in Zoomify with metadata, a link to the viewer of the georeferenced version of the same map and its WMS address for use in one’s own GIS

- 3.3 Map Series

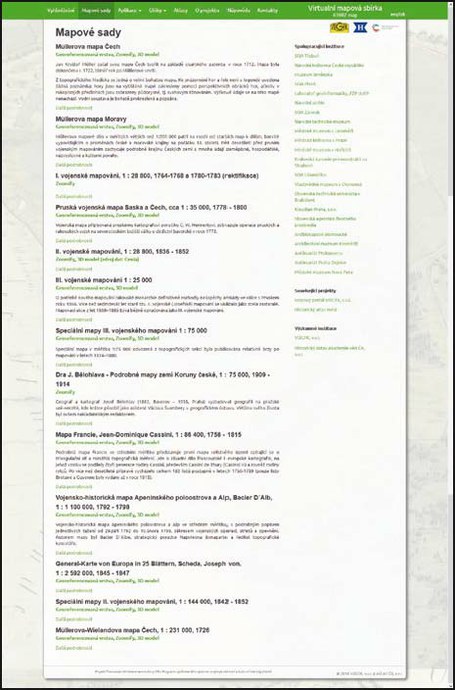

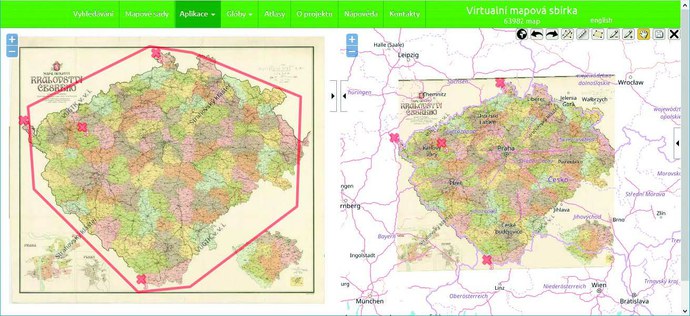

The Web Map Services (WMS/TMS) are used not only for publishing individual commonplace maps, but mainly for publishing important large multi-sheet map series, where preferential georeferencing is useful. Figure 5 shows an overview of map series published on the Chartae-Antiquae.cz portal. Over time, more and more are being added. Maps can be viewed not only in a non-georeferenced format (Zoomify) but mostly in a georeferenced format in the viewer (via) WMS/TMS, as well as in the texture format on a 3D terrain model.

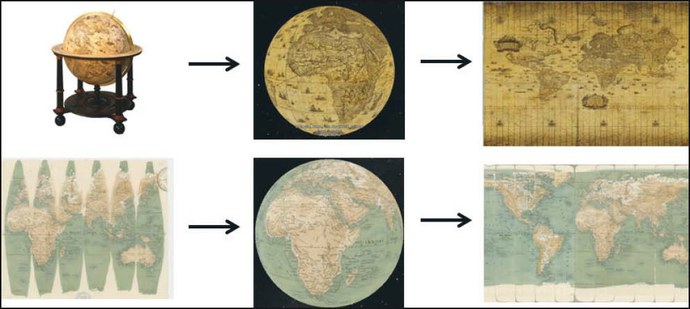

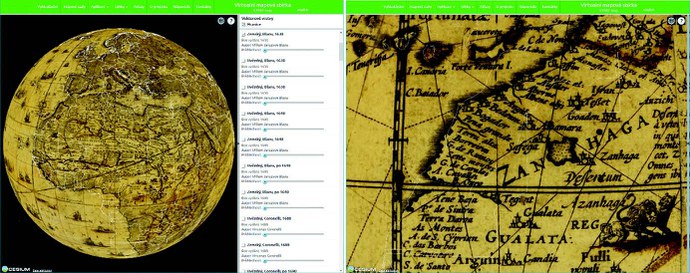

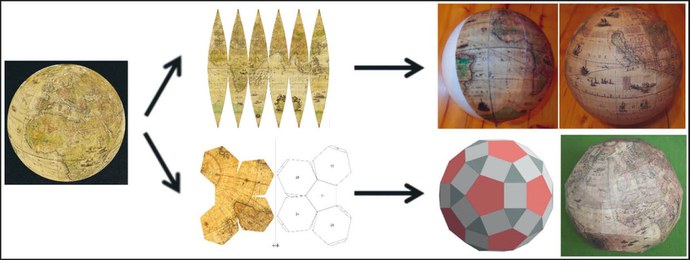

- 3.4 Globe Models and Access to Atlases

Old globes, which are cartographic products as well, can also be digitised. There are basically two options: you either digitise an old surviving globe or you digitise the globe (meridian) strips from which the globe was created. However, the strips have been preserved only exceptionally and, by contrast, globes matching the preserved strips often no longer exist. It is thus even possible to make a virtual reconstruction of old globes where only the relevant strips have been preserved. In both cases, the goal is to create an accurate 3D georeferenced model of a globe and a 2D map created by unrolling the globe on to a flat surface. The procedure is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 5. Map series on the Chartae-Antiquae.cz portal

Fig. 6 A schematic outline of two basic tasks of globe digitisation

The strips are digitised by their scanning and subsequent processing of the resulting raster images. A photogrammetric method is used to digitise real old globes where a 3D model of the globe is created by putting together the photographs scanned on a digitising device. The resulting model should be in such high-resolution that all the details are legible. Its legibility is often better than that of the original.

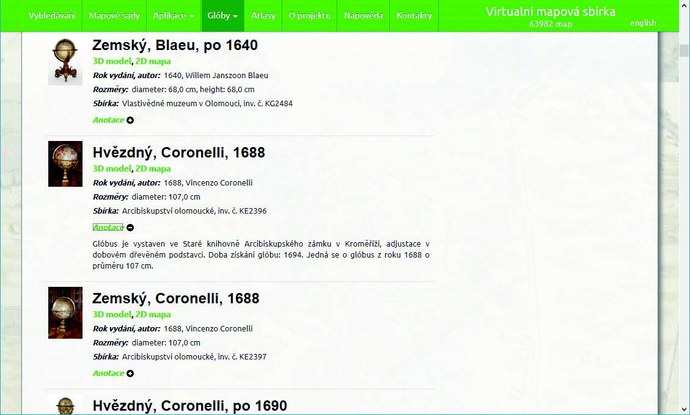

Fig. 7 An example of part of the list of digitised globes

The Chartae-Antiquae.cz portal now offers access to 114 models of old globes both in 3D and in 2D formats. In addition to the actual models, each globe is provided with photos and metadata with annotations - see Fig. 7. 3D models are displayed in the Cesium application. If the graphics card of the user’s PC does not support the Cesium application (applies only to older PCs), it automatically uses Google Earth to show the model. Individual models are displayed as georeferenced layers, so it is possible to compare them with each other by making them transparent. It is also possible to compare the models with the current vector layer showing the landmass and state borders, or with aerial photographs. Comparing two or more globes with each other can be very interesting for users. It is thus possible to trace back, for example, the history of discovery routes and “the state of mapping” of the world at that time, or to see the geodetic data used by the relevant globe author. Fig. 8 shows the method of making the globes accessible on the portal. (For more on digitising globes, see footnotes 12, 13, 14) 12, 13 and 14.

Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLI-B5, 2016, XXIII ISPRS Congress, 12–19 July 2016, Prague, Czech Republic. DOI: 10.5194/isprsarchives-XLI-B5-169-2016. Available at: https://www.int-arch-photogramm-remote-sens-spatial-inf-sci.net/XLI-B5/169/2016/ .

Fig. 8 A 3D model of W. J. Blaeu’s globe from 1630 with a vector layer on the left. Globe close-up on the right.

In addition to the above mentioned task of digitising old globes the result of which is a 3D model of the globe we can, after its successful completion, work reversely. This involves creating printing masters for old globes replicas using these digital 3D models. A schematic drawing of the task is shown in Fig. 9. It is possible to create either printing masters for globe strips to be glued to a sphere of a certain size to create faithful replicas, or printing masters for paper fold-ups, which may come in several types based on the chosen polyhedron that is to replace the sphere. (For more on the reverse task, see footnote 15)15.

Fig. 9 A scheme of the reverse task of globe digitisation, i.e. the creation of printing masters for their replicas. The upper picture shows how to create a faithful replica of a globe sphere from strips, the lower picture shows how to create a paper fold-up.

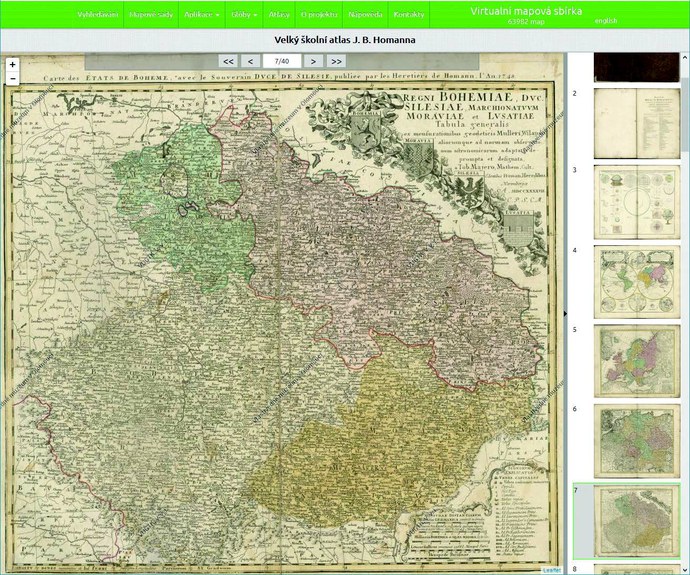

Old atlases are available on the portal in their own viewer. Like globes, they have annotated metadata. At present, 150 old atlases are available there. You can search among them by atlas title, author or date of issue.

Fig. 10 A viewer of old atlases

- 4. Map Applications

To utilise the added value of properly digitised old maps it is necessary to create special map applications. As an example of good practice, we will again use the Chartae-Antiquae.cz portal, which offers various map web applications to users.

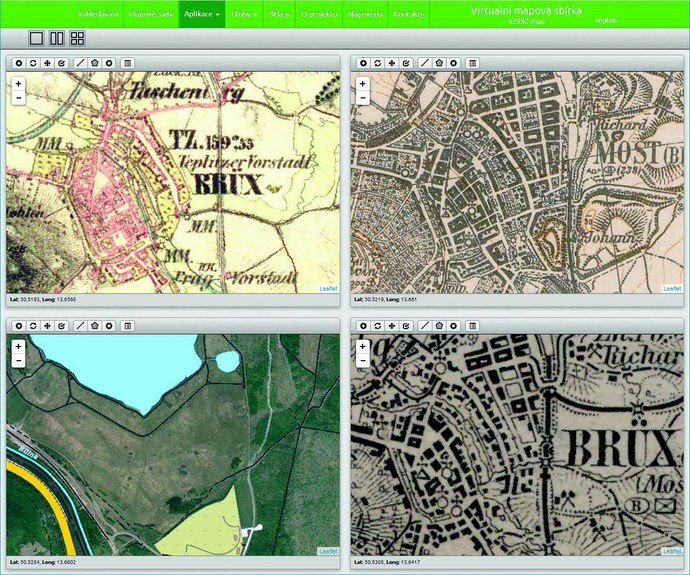

- 4.1 MapComparer

Georeferenced old maps already go beyond paper map possibilities and provide the users with new tools for such work with maps that would not be possible with paper maps. The first big advantage is the possibility to compare two or more different maps. With MapComparer, the user can compare maps from different time periods, maps of different scales and different cartographic projections, which may also come from different map collections. And if they remained in the source paper format they could not be placed on one table next to each other. Viewing of such maps is enabled by MapComparer, a web application available on the portal’s website and the very first web application for comparing old maps at the time of its creation (2012). Only later, following its example, similar applications began to emerge, including on a commercial basis - see, for example, http://www.georeferencer.com/compare#. MapComparer offers two types of map comparing.

The first compares maps in one large map window where the map sources are “opened” and changes in both maps can be compared with the help of a transparency tool. MapComparer can open any map sources found in the portal database - for example, the 3rd Military Survey 1: 25,000 (1876-1880) map or the current orthophoto (aerial image) map and/or maps of the 2nd Military Survey 1: 28,800 (1836–1852). Using the scroll bar, you can make individual maps more transparent and compare changes. You can also add any other maps provided by the WMS, Zoomify or as your own raster image from your PC.

When comparing more than two maps, this method is less practical and confusing for users. Therefore, MapComparer is equipped with a map viewing function in two to four map windows. In each window you can run (display) a different map and visually compare up to four maps at once. Zooming and panning a map in one window also synchronously pans maps in other windows so the user still compares the same location at the same scale and on the same screen. However, the user can upload other maps to each window using multiple layers, which can be opened or closed or made more transparent. Thus they can compare, for example, 10 maps at a time, both visually and by making them transparent.

Fig. 11 The city of Most on four different maps in MapComparer. The 2nd Military Survey (1836–1852) at the top left, the 3rd Military Survey 1 : 25,000 (1874–1938) at the top right, the 3rd Military Survey 1 : 75,000 (1923–1928) at the bottom right and a contemporary orthophoto with selected layers of the ZABAGED map.

Several map series that are most frequently used for tracking changes on old maps are already present in the application as built-in layers. However, the user can add other maps that are provided by anyone via the WMS to the application, such as cadastral maps, geological maps, maps of archaeological sites, etc. In the map window, the user can upload a map that is not provided by the WMS, but is displayed on the website via Zoomify, or a map stored on the user’s computer. However, these maps are not georeferenced and must be controlled separately in the application. It is important to emphasise that to use all these features, the user only needs a web browser and does not have to have any GIS of their own or specialised software.

- 4.2 Automatic Recognition of Map Symbols

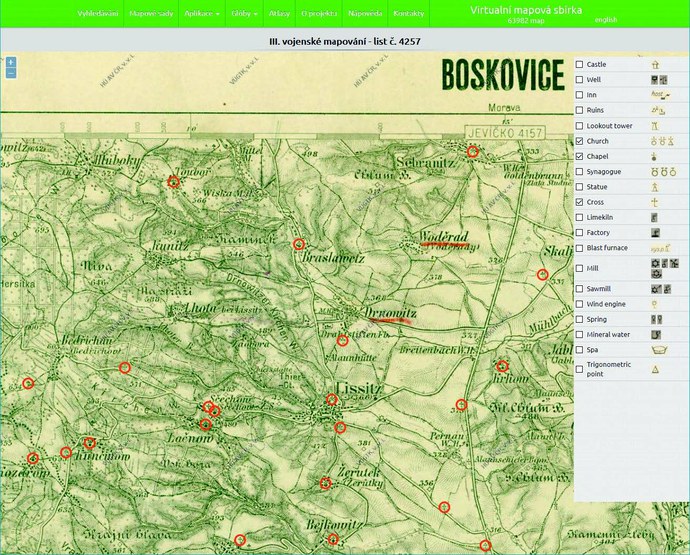

Searching for map symbols on the map can be useful as an application. The portal has an application for searching map symbols in special-purpose maps of the 3rd Military Survey (1: 75,000). These maps have very rich map legends. From the user’s point of view, however, these maps are very confusing due to substantially dense drawings including hatches. For the purpose of fast search, a special application has been developed where the symbols are already automatically searched by the machine method of object recognition in the raster image. The

user only checks the appropriate map symbol in the legend and these symbols are immediately highlighted on the selected map sheet - see Fig. 12.

Fig. 12 Automatic search for churches, chapels and crosses around Lysice near Boskovice

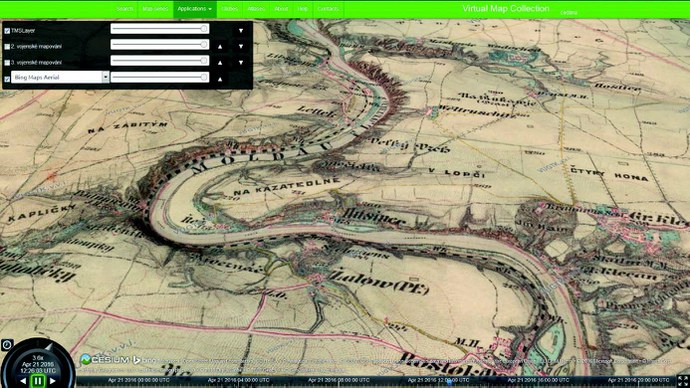

- 4.3 Converting Zoomify to WMS and Displaying the WMS Layer on a 3D Map

Two more applications are available on the portal for more advanced work with maps. The first one converts the map raster image from Zoomify format into a georeferenced format that allows that map to be provided by the WMS service. Therefore, it also contains its own georeferencer (a software application for georeferencing), as georeferencing is required for this conversion. An example of online map georeferencing provided in Zoomify is shown in Fig. 13. This application therefore allows the user to georeference any map provided in the Zoomify format and then display it using a Web Map Service (WMS) e.g. in the already built-in viewer. However, it should be noted that large multi-sheet map series should not be georeferenced simply by using an online georeferencer. No such tool yet provides sufficient accuracy of the resulting georeferencing and, above all, does not provide matching of adjacent map sheets. In these cases, it is necessary to use more complex mathematical methods, which also respect the map projection properties and perform the matching of all map sheets in a seamless raster. (An example of a more complex georeferencing of a multi-sheet map series is described, for example, in footnotes 16 and/or 17)16 17.

Fig. 13 An online georeferencer of maps in Zoomify

Fig. 14 A view of the map provided by WMS/TMS in a 3D map format – an example of the 3rd Military Survey

The second application enables to display the WMS or TMS layer in a 3D map. The application is therefore used to display the already digitised maps provided in the WMS or TMS format in a 3D map (3D model). In order to display a map in a 3D format, the application uses the Cesium library, which uses WebGL (Web Graphics Library). Viewing is therefore not possible in older web browsers. One can pan, rotate, tilt or zoom-in the resulting 3D map model as well as to change the lighting direction by setting the date and time. An example of a map display in a 3D model is shown in Fig. 14.

Detailed instructions for use are available for both applications. Again, it is important to emphasise that the user only needs a web browser to use all these features and does not need any GIS of their own or specialised software.

- 4.4 Using Digitised Maps in User Map Applications

The previous paragraph described the possibility of georeferencing with subsequent map display provided by the standardised WMS service. This also allows a map to be displayed in users’ map applications (in their GIS). This added value compared to paper maps is perhaps - especially for its generality and versatility - the most important of all mentioned so far. If old maps, or where appropriate, their raster images are provided in a georeferenced format in a standardised way (i.e. WMS/TMS), this will allow individual users to create their own applications using this data for special purposes.

As the range of users of old maps is huge and the maps can be used in almost all fields of human activity, it is generally not possible to envisage all user needs in advance and create appropriate tools accordingly to utilise old maps as input background data. Much more efficient, and, in terms of the possibility to support the utilisation of this data, more promising is to make old maps available to users in the above mentioned standardised way, which will also allow the use of cartographic properties of maps. Then, it will only be up to the users to ensure the optimum use of the provided data in their own applications for their own needs and at their own costs.

- 5. Old Map Digitisation Requirements

The next section will not cover detailed technical requirements for the digitisation of old maps. It will rather mention a few principles to be observed at any time, given their importance and experience as well as the above mentioned facts. These principles should also be known to librarians and staff of other memory institutions that own map collections and should be requested from the companies that digitise map collections.

When digitising maps or other documents, it should also be borne in mind that permanent preservation of digital copies is a bigger problem than permanent preservation of paper (printed) documents. Data formats are complex and are constantly evolving, which entails higher costs of the necessary reinvestments into hardware and software. Increasing demands on the quality of raster images of old maps, i.e. on higher scan resolution - dpi, thus result in higher demands on data storage capacities. As the costs of accurate certified cartometric digitisation of large maps are considerable, all data must be well backed up, which again means higher hardware costs.

It is also necessary to take into account the issue of copyright law. Copyright protection continues to be valid for 70 years after the author’s death (or, where appropriate, 70 years after publication, if it is an employee work where the copyright holder is an organisation). These works cannot be made freely available unless a licence agreement has been concluded with the author to make them available. Digitisation is thus used to protect only these works, which is certainly not enough. In addition, if the digitised products are made available by an institution other than their owner, i.e. other than the map collection owning the original paper maps, a special contract must be concluded for this purpose, taking into account the reproduction rights owned by the relevant map collection. Both of these cases also apply to the Chartae-Antiquae.cz Virtual Map Collection where (with a few exceptions) copyrighted maps are not accessible. In the vast majority of cases, there are only older maps, i.e. free-to-reproduce works. Moreover, contracts have been concluded with the holders of all map collections from which the digitised maps come, taking into account the reproduction rights to the accessible maps.

- 5.1 Scanning Accuracy

Scanning of old maps created on the basis of cartographic projections should not be carried out in a way that would prevent the preservation of their cartographic properties. The most important thing is to achieve the highest possible positional accuracy of individual pixels in the raster image. This can only be achieved by using precision cartometric scanners, the positional accuracy of which is regularly checked (certified).

This control measurement, during which the tested scanner takes a raster image of the control grid with subsequent evaluation, is provided by the Office for Surveying and the Czech Surveying and Cadastre Office (ČÚZK) then issues the appropriate certificate for cartometric or orientation scanning according to the achieved accuracy. The testing is governed by Guidelines No. 32 for the scanning of cadastral maps and graphic documentation of earlier land records,18 which provide further details, including the purpose and principles of testing the scanners in accordance with ČÚZK regulations. Scanning of a control square grid is performed (50 mm grid with the size of 700 mm × 550 mm) on non-shrinkable material (astralon plastic foil) measured on a digitiser with a guaranteed accuracy of 0.05 mm. To obtain the certificate, the tested scanner must meet the following requirements:

- - Cartometric scanning requirements: the accuracy with which the raster data is acquired is characterised by a mean coordinate error mxy ≤ 0.10 mm, a mean transformation key error ≤ 0.07 mm, a maximum position deviation ≤ 0.20 mm (if the scanning device used is a cylindrical scanner, a maximum position deviation must be ≤ 0‚30 mm) and a resolution of at least 400 dpi;

- - Orientation scanning requirements: the accuracy with which the raster data is acquired is characterised by a mean coordinate error mxy ≤ 0.15 mm, a mean transformation key error ≤ 0.12 mm, a maximum position deviation ≤ 0.40 mm and a resolution of at least 400 dpi.

However, when evaluating these at first glance seemingly very strict requirements, it must be taken into consideration that, for example, a maximum permissible position deviation of only 0.4 mm for orientation scanning will result in a size error of four metres in the actual point position in a map with a scale of 1: 10,000. Further details on the testing of cartometric scanners are given, for example, in footnote 1919.

- 5.2 Scanning Parameters

It clearly follows from the above that the optical resolution of the scanner should be at least 400 dpi in both directions. It is even strongly recommended to use higher resolution, i.e. 600 or 800 dpi, based on the experience acquired. It should be borne in mind that in order to use the above applications, it is necessary to perform georeferencing of raster images of old maps. However, this requires the resampling of these raster images as part of the process of their transformation, which naturally degrades the quality and readability of the image. The only solution is to have the original raster images in the highest possible resolution and thus have a certain “backup” to enable various operations with these images. Moreover, if we want to use digitised maps in applications that automatically process their raster images (we can use the previously mentioned application for searching map symbols as an example) it becomes apparent that even 400 dpi may not be enough because the error rate of graphical search algorithms increases sharply. And in fact the original non-geo-referenced, i.e. non-resampled (highest quality), raster images are used. In other words, 300 or 400 dpi is enough for a mere viewing of non-georeferenced maps on the screen. But if we want to use maps in a more sophisticated way, which is a clear requirement of today’s readers, we need at least 600 dpi or more. Given the amount of money that needs to be invested in the digitisation of old maps, scanning below 600 dpi can be considered wasted money in terms of future prospects. Over time, maps scanned in this manner will have to be rescanned with higher parameters. The main reason will be the growing demands of readers on using digitised maps in various applications.

To maintain colour fidelity, scanning should be performed at a colour scale of at least 24 bits, including the colour ICC (International Color Consortium profile)20 profile, which has been approved as the international ISO 15076-1: 2005 standard (Image technology colour management – Architecture, profile format and data structure)21. This colour profile is characterised by the colour gamut (achievable colour area in a particular colour space) and the properties of the reproduction device or medium. The information can then be used to accurately reproduce or display colours on a printer, monitor, plotter or another device. ICC profiles are used mainly in DTP applications where they are used for conversion between RGB and CMYK colour spaces and to ensure colour matching when reproducing colours.

- 5.3 Removing Paper Shrinkage

- Paper shrinkage usually accounts for a significant amount of the map drawing deformation. For example, if a map sheet with a scale of 1: 100,000 shrinks by 3 mm over many decades or hundreds of years, which is quite common, this results in an error of 300 meters. The lengths measured and especially the areas calculated are thus inaccurate. To eliminate shrinkage, it is necessary to take into account how it arises. It is a consequence of the paper drying out and aging. At the same time, shrinkage is different in each of the basic directions of a map sheet and, moreover, a completely irregular shrinkage can occur due to such accidents as paper spillage or exposure of part of the sheet to moisture or sun rays, etc. If we accept the hypothesis that the largest differences in shrinkage will be in perpendicular directions, which is given by the manufacturing process (by rolling the paper in paper machines), at least an affine coordinate transformation will be needed to eliminate shrinkage. It will be much better to use projective transformation. However, if we also want to address the issue of the map frame warping, it will be necessary to use a polynomial coordinate transformation, or TPS (Thin plate spline) transformation,22 which will help us best rectify the raster image of the age-shrunk paper map sheet to its original size. However, all this applies only if we know the original (theoretical) size of the map sheets. This is usually known for large (multi-sheet) map series, but may not be known for individual very old maps.

- 5.4 Editing Scans

The actual scanning is usually followed by basic editing of the scans - raster images. They consist in the trimming of the paper edge or map frame, rotating (straightening) of the image or, where appropriate, in removing paper shrinkage. If a proper software automated tool working on the basis of object recognition in raster images (paper edges, map frame, etc.) is used for trimming, the experience with multi-sheet map series shows that it is possible to increase the scanning performance, including pre-processing of scans, up to ten times23 and/or 24.

- 5.5 Duplicate Occurrences of the Same Map

A common issue that also needs to be addressed when digitising maps is how to deal with duplicate occurrences of the same map. It means that the same map appears in a map collection in multiple copies or it is held in the collections of various institutions, and therefore appears multiple times in the summary virtual collection of digitised maps.

It is important to remember that maps are treated differently from ordinary documents. While the content of an ordinary text document is always the same regardless of the print or (usually) edition, this is not the case with maps. The reader obtains the same written information from different copies of the same book. However, it follows from the above that with maps specific factors come into play, such as paper shrinkage, damage to a map sheet including by drawing notes, staining it with coffee, cutting it into sections and mounting it on canvas for convenient folding, ripping a map sheet, additional overprints of nomenclature in another language, additional reprint of another coordinate grid, additional colouring of the content or content changes for different editions of the same map (“content update”). Also, the condition of each copy of the same map is different. It is apparent from all the above that all copies of old maps need to be digitised and that we cannot speak about “duplications in the catalogue”, as librarians are used to doing.

- 6. Conclusion

The purpose of the paper has been to provide librarians and staff of other memory institutions with clear information on how to help readers in certain specific areas, such as old maps. At the same time, the aim has been to provide information on the most important principles that need to be observed when digitising map collections to enable their owners to demand adherence of these principles from digitisation companies. Another useful source of literature is referred to in footnote25 and an example of an advanced sophisticated web application for working with old maps is referred to in footnote26.

In addition to the necessary overview of the largest map collections in the Czech Republic, made available at least in part on the Internet, we have used the Chartae-Antiquae.cz Virtual Map Collection as a good practice example to present various web applications that provide added value for digitised map users, compared to original paper maps. The portal of this Virtual Map Collection thus serves as an expert knowledge system for working with old maps. This gives users a powerful tool for their work. The digitised old maps that have been made available can be used in many fields of human activity, for example for the reconstruction of historical landscape and settlement structures, for various history studies, but also for the purposes of spatial planning to trace back the original condition.

REFERENCES:

AMBROŽOVÁ, Klára, Jan HAVRLANT, Milan TALICH a Ondřej BÖHM, 2016. The process of digitizing of old globe. In: The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLI-B5, 2016, XXIII ISPRS Congress, 12–19 July 2016, Prague, Czech Republic. DOI: 10.5194/isprsarchives-XLI-B5-169-2016. Available at: https://www.int-arch-photogramm-remote-sens-spatial-inf-sci.net/XLI-B5/169/2016/ .

ANTOŠ, Filip, Ondřej BÖHM a Milan TALICH, 2014. Accuracy testing of cartometric scanners for old maps digitizing. In: 9th International Workshop on Digital Approaches to Cartographic Heritage, Budapest, 4–5 September 2014, 8pp. Available at:

http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/publikace/antos_et_all-acuracy_testing.pdf .

ANTOŠ, Filip, Ondřej BÖHM a Milan TALICH, 2011. Automatické zpracování prvního vydání Státní mapy 1 : 5 000 – odvozené pro vystavení na internetu, In: 19. Kartografická konferencia, kartografia a geoinformatika vo svetle dneška, ed. L. Gálová, R. Fencík, Bratislava, 8. – 9. 9. 2011, pp. 16–25.

ČESKÝ ÚŘAD ZEMĚMĚŘIČSKÝ A KATASTRÁLNÍ. Pokyny č. 32 Českého úřadu zeměměřického a katastrálního ze dne 28. dubna 2004, č.j. 1014/2004-22 pro skenování katastrálních map a grafických operátů dřívějších pozemkových evidencí, ve znění dodatku č. 1 ze dne 15. 2. 2005 č.j. 613/2005-22, dodatku č. 2 ze dne 8. 3. 2005 č.j. 1503/2005-22, dodatku č. 3 ze dne 7. 4. 2006 č.j. 1223/2006-22, dodatku č. 4 ze dne 16. 5. 2006 č.j. 2321/2006-22, [cit. 15. 3. 2019]. Available at: https://www.cuzk.cz/Predpisy/Resortni-predpisy-a-opatreni/Pokyny-CUZK-31-42/Pokyny_32.aspx

DF11P01OVV021 – Kartografické zdroje jako kulturní dědictví. Výzkum nových metodik a technologií digitalizace, zpřístupnění a využití starých map, plánů, atlasů a glóbů. (2011–2015, MK0/DF). https://www.rvvi.cz/cep?s=jednoduche-vyhledavani&ss=detail&n=0&h=DF11P01OVV021 [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

HAVRLANT, Jan, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Milan TALICH, Ondřej BÖHM, 2017. Digital models of old globes created from globe segments. In: 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2017, www.sgem.org, SGEM2017 Conference Proceedings, ISBN 978-619-7408-03-4, ISSN 1314-2704, 29 June – 5 July, 2017, Vol. 17, Issue 23, 473–480 pp, DOI: 10.5593/sgem2017/23/S11.058, https://sgemworld.at/sgemlib/spip.php?article9485 .

HAVRLANT, Jan, Milan TALICH a Klára VACKOVÁ, 2018. The creation of cartographic data for replicas of old globes. In: 18th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management (SGEM), Volume 18, Issue 2.3, Sofia, 2018, pp. 623–633, ISSN 13142704, DOI: 10.5593/sgem2018/2.3/S11.079,

https://sgemworld.at/sgemlib/spip.php?article12691 .

MEZINÁRODNÍ STANDARD ISO 15076–1:2005 (Image technology colour management – Architecture, profile format and data structure). Dostupné z: http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=40317, ISO 15076–1:2005 Image technology colour management -- Architecture, profile format and data structure. Part 1: Based on ICC.1: 2004–10, [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

TALICH, Milan, 2012. Trendy výzkumu možností využívání starých map digitálními metodami. Kapitola v knize: Krajina jako historické jeviště. K poctě Evy Semotanové. Praha: Historický ústav (eds. Chodějovská, E.; Šimůnek, R.), pp. 373–386, ISBN 978-80-7286-199-6. Available at: http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/publikace/Krajina_Talich.pdf .

TALICH, Milan, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Jan HAVRLANT a Ondřej BÖHM, 2015. Digitization of Old Globes by a Photogrammetric Method. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography 2015. Cartography – Maps Connecting the World. 27th International Cartographic Conference 2015 – ICC2015. Editors: Claudia Robbi Sluter, Carla Bernadete Madureira Cruz, Paulo Márcio Leal de Menezes. Springer International Publishing. pp. 249–263. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-17738-0_17, ISBN: 978-3-319-17737-3, ISSN 1863-2246.

TALICH, Milan, Filip ANTOŠ a Ondřej BÖHM, 2011. Automatic processing of the first release of derived state maps series for web publication. In: 25th International Cartographic Conference (ICC2011) and the 15th General Assembly of the International Cartographic Association, Paris, France, 3 – 8 July 2011, section “C3-Digital technologies and cartographic heritage”. ISBN 978-1-907075-05-6. Available at: http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/publikace/co-268.pdf .

TALICH, Milan, Ondřej BÖHM a Lubomír SOUKUP, 2018. Classification of digitized old maps. In book: Advances and Trends in Geodesy, Cartography and Geoinformatics, Eds: Molcikova, S., Hurcikova, V., Zeliznakova, V., P. Blistan. ISBN 978-0-429-50564-5, CRC PRESS-TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP, April 2018, 197–202 pp, DOI: 10.1201/9780429505645-32,

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780429012891/chapters/10.1201%2F9780429505645-32 .

TALICH, Milan, Lubomír SOUKUP, Jan HAVRLANT, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Ondřej BÖHM a Filip ANTOŠ, 2013a. Georeferencing of the Third Military Survey of Austrian Monarchy. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Cartographic Conference, Dresden, Germany, 25–30 August 2013, pp. 898–899, International Cartographic Association, ISBN 78-1-907075-06-3, Available at: https://icaci.org/files/documents/ICC_proceedings/ICC2013/_extendedAbstract/266_proceeding.pdf .

TALICH, Milan, Lubomír SOUKUP, Jan HAVRLANT, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Ondřej BÖHM a Filip ANTOŠ, 2013b. Nový postup georeferencování map III. vojenského mapování. Kartografické listy, 21(2), 35-49. Bratislava: Kartografická spoločnosť Slovenskej republiky v spolupráci s Geografickým ústavom Slovenskej akadémie vied a Prírodovedeckou fakultou Univerzity Komenského v Bratislave, Slovensko. ISSN 1336-5274.

TALICH, Milan, Eva SEMOTANOVÁ a kol., 2015. Kartografické zdroje jako kulturní dědictví. Výzkum nových metodik a technologií digitalizace, zpřístupnění a využití starých map, plánů, atlasů a glóbů. Elektronická publikace, Praha: Historický ústav AV ČR, vol. 64, ISBN 978-80-7286-262-7, p. 114. Available at: http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/katalog_2015.pdf .

VIRTUÁLNÍ MAPOVÁ SBÍRKA CHARTAE-ANTIQUAE.CZ. Virtuální mapová sbírka [online]. [cit. 2020-03-15]. Available at: http://www.chartae-antiquae.cz .

Notes

1 http://www.chartae-antiquae.cz, Virtuální mapová sbírka Chartae-Antiquae.cz. [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

2 DF11P01OVV021 – Kartografické zdroje jako kulturní dědictví. Výzkum nových metodik a technologií digitalizace, zpřístupnění a využití starých map, plánů, atlasů a glóbů. (2011–2015, MK0/DF).

https://www.rvvi.cz/cep?s=jednoduche-vyhledavani&ss=detail&n=0&h=DF11P01OVV021 [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

3 http://www.chartae-antiquae.cz, Virtuální mapová sbírka Chartae-Antiquae.cz. [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

4 http://www.opengeospatial.org/standards/wms, The OpenGIS® Web Map Service Interface Standard (WMS), [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

5 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tile_Map_Service, Tile Map Service (TMS), [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

6 TALICH, Milan, Lubomír SOUKUP, Jan HAVRLANT, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Ondřej BÖHM a Filip ANTOŠ. Georeferencing of the Third Military Survey of Austrian Monarchy. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Cartographic Conference, Dresden, Germany, 25–30 August 2013, pp. 898–899, International Cartographic Association, ISBN 78-1-907075-06-3, Available at: https://icaci.org/files/documents/ICC_proceedings/ICC2013/_extendedAbstract/266_proceeding.pdf.

7 TALICH, Milan, Lubomír SOUKUP, Jan HAVRLANT, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Ondřej BÖHM a Filip ANTOŠ. Nový postup georeferencování map III. vojenského mapování. Kartografické listy, 21 (2), Bratislava, Kartografická spoločnosť Slovenskej republiky v spolupráci s Geografickým ústavom Slovenskej akadémie vied a Prírodovedeckou fakultou Univerzity Komenského v Bratislave, Slovensko, 2013, pp. 35–49, ISSN 1336-5274.

8 TALICH, Milan. Trendy výzkumu možností využívání starých map digitálními metodami. Kapitola v knize: Krajina jako historické jeviště. K poctě Evy Semotanové. Praha: Historický ústav, 2012 - (eds. Chodějovská, E.; Šimůnek, R.), pp. 373–386, ISBN 978-80-7286-199-6. Available at: http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/publikace/Krajina_Talich.pdf.

9 http://www.opengeospatial.org/standards/wms, The OpenGIS® Web Map Service Interface Standard (WMS), [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

10 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tile_Map_Service, Tile Map Service (TMS), [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

11 http://www.opengeospatial.org/, The Open Geospatial Consortium, [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

12 TALICH, Milan, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Jan HAVRLANT a Ondřej BÖHM. Digitization of Old Globes by a Photogrammetric Method. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography 2015. Cartography – Maps Connecting the World. 27th International Cartographic Conference 2015 - ICC2015. Editors: Claudia Robbi Sluter, Carla Bernadete Madureira Cruz, Paulo Márcio Leal de Menezes. Springer International Publishing. pp. 249–263, 2015, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-17738-0_17, ISBN: 978-3-319-17737-3, ISSN 1863-2246.

13 AMBROŽOVÁ, Klára, Jan HAVRLANT, Milan TALICH a Ondřej BÖHM. The process of digitizing of old globe. In: The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and

14 HAVRLANT, Jan, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Milan TALICH, Ondřej BÖHM. Digital models of old globes created from globe segments. In: 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2017, www.sgem.org, SGEM2017 Conference Proceedings, ISBN 978-619-7408-03-4 / ISSN 1314-2704, 29 June – 5 July, 2017, Vol. 17, Issue 23, 473–480 pp, DOI: 10.5593/sgem2017/23/S11.058, https://sgemworld.at/sgemlib/spip.php?article9485 .

15 HAVRLANT, Jan, Milan TALICH a Klára VACKOVÁ. The creation of cartographic data for replicas of old globes. In: 18th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management (SGEM), Volume 18, Issue 2.3, Sofia, 2018, pp. 623–633, ISSN: 13142704, DOI: 10.5593/sgem2018/2.3/S11.079,

https://sgemworld.at/sgemlib/spip.php?article12691 .

16 TALICH, Milan, Lubomír SOUKUP, Jan HAVRLANT, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Ondřej BÖHM a Filip ANTOŠ. Georeferencing of the Third Military Survey of Austrian Monarchy. In: Proceedings of the 26th International Cartographic Conference, Dresden, Germany, 25–30 August 2013, pp. 898–899, International Cartographic Association, ISBN 78-1-907075-06-3, Available at: https://icaci.org/files/documents/ICC_proceedings/ICC2013/_extendedAbstract/266_proceeding.pdf

17 TALICH, Milan, Lubomír SOUKUP, Jan HAVRLANT, Klára AMBROŽOVÁ, Ondřej BÖHM a Filip ANTOŠ. Nový postup georeferencování map III. vojenského mapování. Kartografické listy, 21 (2), Bratislava, Kartografická spoločnosť Slovenskej republiky v spolupráci s Geografickým ústavom Slovenskej akadémie vied a Prírodovedeckou fakultou Univerzity Komenského v Bratislave, Slovensko, 2013, pp. 35–49, ISSN 1336-5274.

18 https://www.cuzk.cz/Predpisy/Resortni-predpisy-a-opatreni/Pokyny-CUZK-31-42/Pokyny_32.aspx , Pokyny č. 32 Českého úřadu zeměměřického a katastrálního ze dne 28. dubna 2004, č.j. 1014/2004-22 pro skenování katastrálních map a grafických operátů dřívějších pozemkových evidencí, ve znění dodatku č. 1 ze dne 15. 2. 2005 č.j. 613/2005-22, dodatku č. 2 ze dne 8. 3. 2005 č.j. 1503/2005-22, dodatku č. 3 ze dne 7. 4. 2006 č.j. 1223/2006-22, dodatku č. 4 ze dne 16. 5. 2006 č.j. 2321/2006-22, [cit. 15. 3. 2019 ].

19 ANTOŠ, Filip, Ondřej BÖHM a Milan TALICH. Accuracy testing of cartometric scanners for old maps digitizing. In: 9th International Workshop on Digital Approaches to Cartographic Heritage, Budapest, 4–5 September 2014, 8pp. Available at:

http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/publikace/antos_et_all-acuracy_testing.pdf

20 http://www.color.org/, International Color Consortium, [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

21 http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=40317, ISO 15076–1:2005 Image technology colour management -- Architecture, profile format and data structure. Part 1: Based on ICC.1: 2004–10, [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

22 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thin_plate_spline, Thin plate spline. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, [cit. 15. 3. 2019].

23 ANTOŠ, Filip, Ondřej BÖHM a Milan TALICH. Automatické zpracování prvního vydání Státní mapy 1 : 5 000 – odvozené pro vystavení na internetu, in: 19. Kartografická konferencia, kartografia a geoinformatika vo svetle dneška, ed. L. Gálová – R. Fencík, Bratislava, 8. – 9. 9. 2011, pp. 16–25.

24 TALICH, Milan, Filip ANTOŠ a Ondřej BÖHM. Automatic processing of the first release of derived state maps series for web publication. In: 25th International Cartographic Conference (ICC2011) and the 15th General Assembly of the International Cartographic Association, Paris, France, 3 – 8 July 2011, section „C3-Digital technologies and cartographic heritage“. ISBN: 978-1-907075-05-6. Available at: http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/publikace/co-268.pdf .

25 TALICH, Milan, Eva SEMOTANOVÁ a kol. Kartografické zdroje jako kulturní dědictví. Výzkum nových metodik a technologií digitalizace, zpřístupnění a využití starých map, plánů, atlasů a glóbů. Elektronická publikace, Praha 2015: Historický ústav AV ČR, vol. 64, ISBN 978-80-7286-262-7, pp 114. Available at: http://naki.vugtk.cz/media/doc/katalog_2015.pdf .

26 TALICH, Milan, Ondřej BÖHM a Lubomír SOUKUP. Classification of digitized old maps. In book: Advances and Trends in Geodesy, Cartography and Geoinformatics, Eds: Molcikova, S.; Hurcikova, V.; Zeliznakova, V.; Blistan, P., ISBN: 978-0-429-50564-5, CRC PRESS-TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP, April 2018, 197–202 pp, DOI: 10.1201/9780429505645-32,

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780429012891/chapters/10.1201%2F9780429505645-32 .